Can you repair a shock absorber? DIY motorcycle suspension

By John Milbank

Consumer Editor of Bennetts BikeSocial

09.11.2021

Michael Hancock, K-Tech suspension engineer.

We all know the importance of proper motorcycle maintenance – it’ll keep your bike running at its best and safest. But to many of us, the suspension is considered a sealed unit; a part that can be ignored until it starts leaking.

The degradation in quality of your bike’s suspension is so gradual that it’s easy to miss the fact that your motorcycle doesn’t handle as well as it used to. But it’s not just about riding fast; keeping the wheels in contact with the road is vital to your safety on any ride.

Michael Hancock has been an engineer at K-Tech suspension in Derbyshire for more than 14 years, rebuilding shocks and forks made by Öhlins, WP, KYB, Sachs and many other brands, as well as working with TT, Dakar, GP and BSB teams on K-Tech’s own race-winning UK-made suspension.

As part of our series of DIY motorcycle maintenance articles, I’ve been servicing my 1999 Kawasaki ZX-6R, but rebuilding or repairing a shock absorber is not a job that can be done at home; it requires specialist tools and knowledge that means even main dealers don’t typically service them…

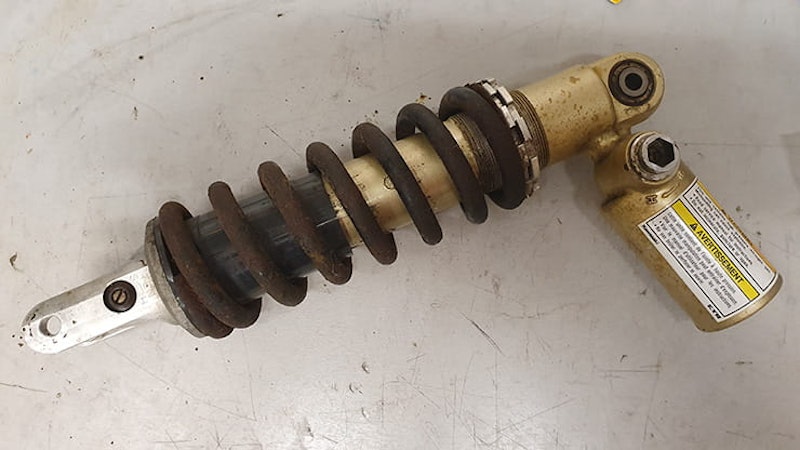

This is the shock off my 1999 Kawasaki ZX-6R – the reservoir poking out of the body is a sure indicator that it can be serviced.

Can my motorcycle shock absorber be repaired or serviced?

Maybe. As a rule of thumb, if your original equipment (OE – the one that came with the bike) shock absorber has a reservoir poking out of the body or at the end of a hose, it almost certainly can. In that case, K-Tech would usually charge about £145 (inc VAT) for a complete rebuild including oil, seals and bushes; the price might vary by about a fiver either way, depending on the parts needed.

Shocks with a reservoir have the body filled with oil, then the oil kept under pressure by gas behind a piston or rubber bladder to stop air bubbles building up through cavitation, while providing ‘space’ for the damping rod to move into the body.

That reservoir can be inside the shock body, sticking out of it, or attached by a hose; the further the reservoir is from the moving shock, the less likely it is to be affected by increases in temperature when the shock is worked hard. Nitrogen is used in the reservoir as its pressure is more stable under varying temperatures than air. You can find a great guide to the different types of shocks by clicking here.

Unike OE units, aftermarket single-body shocks are often also rebuildable, and would usually cost the same £145 to service; you can always check by contacting K-Tech.

The Yamaha MT-07 is just one of many bikes that uses a simple – and non-rebuildable – emulsion shock

What shocks can’t be repaired and why?

A lot of bikes have more simple emulsion shocks, which are a single body but the shock is filled with oil and gas together, which gives the damping rod space to move into the shock body as it’s compressed. As it moves rapidly in and out, the air mixes into the oil, which is when the shock will typically be performing as it’s expected to.

This system works okay, but it’s susceptible to inconsistent damping, especially under hard use. It also can’t economically be serviced – while the pressure could be released, the shock stripped then rebuilt (assuming it’s not crimped closed), it’d need a Schrader valve fitting in order to be able to recharge the gas, and there’d always be the worry that the shock might not be perfectly sealed; it’d not be worth the labour costs compared to a replacement.

The Yamaha MT-07 shock is a good example; replacing it with a K-Tech Razor-Lite would only cost £415, and you’d be getting a UK-made shock with very high-quality internals that can be adjusted for rebound damping and preload, and will be supplied with settings and a spring to suit your weight. While this is a single-unit shock, it has a nitrogen-filled reservoir inside the body to keep the oil and gas separate, and it’s fully rebuildable, so will last a lifetime. That compares very well to the poorer-performing OE unit, which costs £446.58.

The K-Tech Razor-Lite is a very well-priced high-performance shock that can replace un-servicable units on many of today’s bikes.

When you buy a higher-quality shock, you’re potentially getting something with tighter tolerances and adjusters that make much more of a difference (OE suspension often has adjusters that aren’t as effective as they could be). You’re also getting the opportunity to buy suspension that’s perfectly set up for your weight and your riding style. And service parts should be much more readily available.

The construction – both externally and internally will vary between brands – K-Tech for instance uses high-quality hard-anodising on its internal components to prolong the life of the oil, which reduces the chances of the damping fading. A top-quality race shock – like the DDS units from K-Tech – can do a full season of TT racing and will perform the same before the racing and after (K-Tech has a shock dyno to test and tune the damping of its shock absorbers).

Maxton and Nitron are the other leading UK manufacturers of aftermarket and race shocks, while at the lower-priced end of the market, but all still rebuildable for servicing, a basic shock from Wilbers would cost an MT-07 owner £363, a Hagon £299.50, while a YSS would be £290.52 from Wemoto.

How long should my shock absorber last?

Ideally, suspension should be serviced every three years if you want to really keep it working at its best, though five years should be okay for most road riders. Racers (especially motocross) will of course do it a lot more frequently.

An OE emulsion unit will typically be considered acceptable until it starts to leak as the gas is in the oil anyway, and it’s designed to damp with that emulsion. The damping performance will still degrade over time though, and it’s less likely to be a great unit from the outset.

On higher-performance shocks, where the gas and oil are kept separate, over time the gas will leak into the oil, causing the damping to become inconsistent. You won’t notice it gradually over time, but the difference is striking once it’s replaced.

The shock on my ZX-6R has only covered 18,000 miles, but it’s 20 years old so it well overdue a service…

Without a hugger, the shock is in the ideal place to catch road muck slung from the rear tyre. Keep it clean…

How do I look after my shock absorber?

While not an owner-serviceable part, you should still maintain your shock absorber. “After a wet ride,” says Michael, “give it a spray with penetrating fluid, especially around the damping rod where it goes into the shock body. This will help keep the dirt and moisture from corroding the shaft and the seal.”

Keep an eye out for any oil leak around the damping rod as running the shock dry will very quickly damage it; at best it’ll take longer and be more expensive to service as more parts will need replacing. At worst it’ll be scrap and cost you a lot more than £150 every three to five years in servicing.

Considering that a complete fork service – with new seals and oil – costs the same at K-Tech, keeping your suspension in top condition really should be considered part of a long-term service schedule.

Some shocks, like this one, have a plastic sleeve that ‘protects’ the damping rod, but it also traps dirt and water inside. Michael also doesn’t recommend the use of shock covers, as any moisture and grime that gets in will be trapped, accelerating the corrosion of your suspension and preventing you from keeping it clean.

Most of K-Tech’s suspension servicing tool are made by the company itself

How do I know when my shock absorber needs servicing or replacing?

Unless its spewing oil, you might not notice your bike’s handling getting worse as the damping performance degrades very gradually over time. You could try riding a new bike to compare it, but it’s rarely that easy.

We all know how important it is to change the oil in our bike engines every year but there’s a lot less oil in a shock (or fork), and in many cases it’s having to work a lot harder. Add the fact that the pressurised gas inside will gradual make its way into the oil of a non-emulsion shock, and it becomes clear why a service is worthwhile.

Besides corroding, springs don’t wear out over time unless they’re the wrong ones and get ‘coil-bound’, which is when the coils press against each other. The reason to change the spring would be to match your weight (at K-Tech, a new spring costs £85).

Electronic suspension contains shims and valves just like traditional kit

Can electronic suspension be serviced?

The only real difference between standard and electronic suspension is motors that turn the adjusters and some sensors; it’s still an oil-filled unit with valves and shims.

When rebuilding race suspension, the electronic kit is typically removed by K-Tech, but a road-rider’s electronic suspension will usually cost the same to service as any other – around £145 for the shock and £155 for the forks. And maintenance is just as vital; of the two electronic FJR1300 shocks that Michael’s rebuilt, both of them needed the damper rods re-chroming due to being run dry after they leaked their oil.

K-Tech motorcycle shock rebuild review

K-Tech Suspension typically services forks and shocks in around a week, though in the peak season – early in the year when race teams are preparing – it can take up to two weeks; work can be booked in online, and if you do call, you’ll likely be talking to Michael, who’ll be doing the work.

Here we’ll follow the process for rebuilding the shock from my 1999 Kawasaki ZX-6R…

K-Tech doesn’t offer a ride-in service; you need to supply your shock or forks loose; I cleaned mine as best I could before it got to Michael. The first step is removing the spring; while this one’s nasty looking, it still works fine. If you want to re-paint a spring, you’ll have to get this done yourself. A spring won’t really wear out (apart from rotting through), and if you’re working on a classic rebuild or a custom, you might want to have the original spring refinished.

With the spring removed, Michael’s able to slide the plastic cover off – as he expected, the rubber bump-stop has rotted away. Not a problem – K-Tech keeps a huge stock of spares at all times; the only reason a service might be delayed is if the damper rod is corroded, or in the case of forks, they’re bend or pitted. Creased fork legs can’t be repaired as the metal has been weakened, but K-Tech can source new ones.

After releasing the pressure in the gas reservoir of a shock (if there’s any left), Michael checks the condition of the damper rod. Besides knowing if the service is going to be delayed while it’s sent away for chroming, it’s a good indicator of the condition of the rest of the unit. This one is fine, which means it hasn’t been run dry and will likely be a relatively standard rebuild.

The damper assembly is then unscrewed from the base of the shock then removed

Pouring the old oil out shows just how much gas has leaked into the oil – this is totally normal, and why a service every three to five years is so important. This shock isn’t working anywhere close to how it should.

The cover on the back of the reservoir is shocked out on these Kayaba units by tapping with a mallet, then a special tool is used to draw the Schrader valve and bladder assembly out. The bladder on this 20-year-old shock is fine, but if it were damaged it’d be easily replaced.

With the compression adjuster removed and the damper rod out, the parts are cleaned.

Because the piston and shims are secured to the damper rod with a peened-over nut, Michael turns the end off on the lathe and is then able to disassemble the damper

The shock body and other larger pieces are thoroughly cleaned in a parts washer. It’s vital that everything is absolutely spotless in a shock or fork rebuild, as any contamination will eventually find its way to the shims and valves, compromising the performance of the suspension.

The Teflon guide in the bottom of the shock that the damper rod slides in is removed using a large tap to grip it, then pushed out using a press, before a new guide is inserted.

All the clean parts laid out ready for assembly

Each shim is cleaned as the damper rod assembly is reassembled, after the thread on the rod end has been cleaned up with a die. It’s the attention to detail that does into the rebuild that makes the £145 charge seem so reasonable.

In this case we’re keeping the damping the same as stock, but for a racer – or anyone with specific requirements – the shock can be re-valved to suit where the bike’s being ridden, the rider’s weight and their style. Re-valving a shock puts the cost up to about £250 but compare that to the price of a brand new shock…

New seals are fitted and the shock is carefully reassembled. K-Tech’s seal kits have everything needed for the work and are sourced direct from the manufacturers of the original parts. Only the bump-stop and bladder aren’t in the kit as they don’t always need replacing and are bought from the shock manufacturer.

Using an adaptor in place of the compression adjuster, the shock is filled with fresh oil in a vacuum chamber over a period of about ten minutes to ensure all the air is pulled from the fluid.

The oil is brimmed after the adaptor is removed, then the compression adjuster is re-fitted, before the reservoir is re-charged with nitrogen to 10 Bar (145psi).

Finally, the spring is refitted (or a new one installed), then the settings are adjusted based on K-Tech’s experience and the rider’s needs. We were unable to determine the rate of original spring fitted to the ZX-6R, so opted to install a new K-tech one that’s matched to my weight; they’re available in the company’s trade-mark red, as well as black and yellow or white for Öhlins and WP shocks.

Is it worth having a motorcycle shock rebuilt?

Before taking the shock to K-Tech, I made a point of really concentrating on how the bike felt on a variety of roads. It was okay; for a 20 year old bike it handled fine and felt as you’d expect of a sports bike; a bit choppy.

With the rebuilt shock fitted, the difference was incredible; bumps on A-roads were smoothed out beyond recognition, and my confidence on back-roads was noticeably higher. It’s winter as I first try it, so there’s not the opportunity to really push the bike, but I lent it to BikeSocial’s Steve Lamb – when he got off the bike he couldn’t stop raving about it; “It’s brilliant – it feels so smooth and tight. Just like a brand new bike!”

The rebuilt shock had been the last step in servicing everything on the bike, and at £150 it’s well worth the money. When buying used bikes in future, I’ll always try to get something with a rebuildable shock, and I’ll always have the front and rear serviced. Suspension is critical to a good-performing bike; I’ll never ignore it again.

How motorcycle suspension is serviced

Watch as Michael rebuilds a set of 95,000 mile forks

Watch as Michael rebuilds a set of 95,000 mile forks