Riding Skills: How to read traffic, and survive

BikeSocial Road Tester. As one half of Front End Chatter, Britain’s longest-running biking podcast, Simon H admits in same way some people have a face for radio, he has a voice for writing.

09.08.2022

Why we need to read traffic...

There are 32.9 million cars on UK roads. There are nearly 4.6 million vans, half a million HGVs and over a million other vehicles (anything from milk floats to double decker busses). There are 1.4 million motorbikes – so on the roads, we're outnumbered by 30 to 1. They have the numerical advantage.

Traffic is literally all around us, so you'd think some level of inappropriate interfacing would be inevitable. And it is. As motorcyclists, our threat level is highest in traffic. Over 75% of all motorcycle accidents involve another vehicle – which doesn't mean other vehicles cause 75% of motorcycle accidents; sometimes it's the rider's fault, sometimes it isn't. But determining blame is for police, insurance companies, courts and coroners to argue later: for us right here-and-now, the immediate goal isn't to work out whose fault it is, it's to get home from every ride unscathed – and every ride involves interacting with traffic. Which is why we need to 'read' traffic – to be able to spot behaviour, predict patterns, and understand the dynamics of a mass of big, large boxes all driven by individuals from a cross-section of humanity.

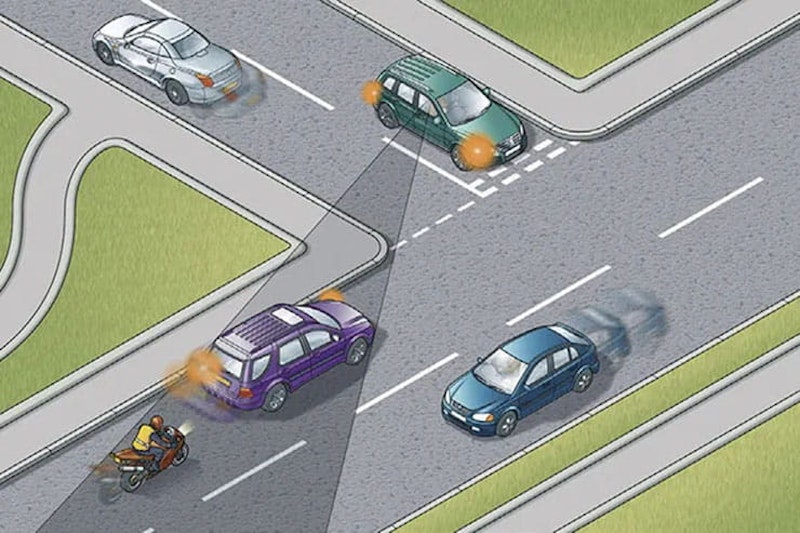

Rule 211 of the Highway code tells road users to look out for motorcyclists and cyclists at junctions. Image from The Highway Code

Lesson One: No-one follows all the rules all the time

Cynics are sniffy about the Highway Code, but it's a set of instructions to designed allow the greatest number of people with the widest range of driving skills, from numpties to racing drivers, to all safely have access to personal transport at the same time. And truth is, if we all religiously obeyed the HC we wouldn't need to read traffic at all. Riding a bike would be like joining a great constellation of vehicles, all moving in a carefully choreographed ballet and never bumping into anything because everyone knows every rule intimately and follows them all precisely. It might not sound much fun, but at least it would be predictable.

No-one follows the Highway Code religiously. Even the most sanctimonious road safety nerd is guilty of the odd transgression. We all – drivers and riders – cherry-pick the bits of the HC we think matter, and discard, flout or remain ignorant of the bits we don't. It only takes a mile on a motorway to see how closely lane discipline is observed, or speed limits, or braking distances. It only takes a minute in town to see how many drivers don't know roundabout lane priority, or how many lapses of concentration there are, or drivers on phones, arguing with a passenger, falling asleep, or eating sandwiches and steering with their knees. From plain ignorance to a momentary loss of concentration to criminal negligence; a short ride will encounter numerous examples of 'bad' driving (and motorcyclists aren't absolved).

Lesson Two: Do your own thing

An inevitability of all traffic breaking some of the rules some of the time is it means we, as individual riders, can't put our faith (and safety) on the rules: we can't assume everyone is following, or even knows, the HC. Sounds obvious, but it has profound implications: it means we have to break the rules too, especially if we want to survive. Vigilance, or being careful, isn't enough – the responsibility for our own safety is entirely, firmly, squarely, unavoidably, in our own hands. We have to do what it takes to avoid contact with traffic (because we'll be the loser), and that – logically – means making our own rules.

Managing our safety when riding in traffic is our responsibility, and ours alone. We are masters of our own fate. If you ever hear, 'That driver was in the wrong, so it's not my fault!' – then that's a fundamental mistake; it's absolutely the wrong mindset to have on a bike. Our safety is our responsibility.

So thanks, Highway Code, but we'll take it as guidance, not for slavish obeyance – if it's a choice between doing what it says in the book or doing what we need to do to not get hurt, let's do the other thing instead.

Lesson Three: Expect the unexpected

Having said that, most of the time traffic moves within a reasonably predictable set of HC-based behaviours. But that can lull us into a false sense of security. We assume traffic will behave a certain way because it normally does. When it suddenly doesn't – when it deviates from the expected and becomes unpredictable – that's when we need to be on high alert because it can go from no problem to big problem for a vulnerable motorcyclist very quickly. Never trust traffic to do what it's supposed to do, or behave the way it's supposed to behave. Always expect the unexpected, and learn the most likely ways it deviates from the norm. Because some unexpected traffic behaviour is less unexpected than others.

Lesson Four: Anticipate a negative, react before it happens

By spotting the potential for a collision, we can react to avoid it before it happens. Again, sounds obvious. But our instinct is to not take physical avoiding action until a threat becomes inevitable. It's flight or fight behaviour in action: see a threat, freeze, threat develops, then we react when it might already be too late.

On a bike, on the road, caution is always the right option. So when we're approaching junction, a driveway or a slip road (and remember, vehicles are just as likely to turn across our path as pull into it!), it's not enough to merely see the potential threat. We have to react before it develops, even though we have right of way. If there's a car at a junction, don't just cover the brakes, don't just pre-load the levers in case and don't rely on eye contact with the driver (I've had them look directly at me and still pull out!). We should roll off the throttle and, in some cases, even start to brake before we know if there's a problem. Yes, it might interrupt our ride a little – but not as much as ploughing into a car would.

Lesson Five: Develop a riding radar

It helps us cope with managing traffic if we break it into regions of threat, or zones of interference. Vehicles don't fall out of the sky or pop up from beneath us (although they probably would if they could), so traffic has six significant vectors:

Vehicles in front of us travelling in our direction

Vehicles behind us travelling in our direction

Vehicles alongside us travelling in our direction (on roundabouts, on multi-lane roads)

Vehicles coming towards us (hopefully on the opposite side of the road)

Vehicles waiting to pull into the road from either side

Static vehicles parked at the side of the road

There are subtleties to this list but, by and large, they're the areas of traffic we need our 'radar' tuned into; the zones of interference that matter. Think of it as our personal space on the road.

The above is a static snapshot: in reality, our riding environment is constantly shifting and changing, generating a flood of information pouring through our eyeballs and into our brains. In fact, it's far more than we've evolved to cope with – our brains are big, but not that big. Novice riders, unused to the deluge of visual information during a ride in traffic, can easily feel overwhelmed and even freeze up completely – literally going into overload paralysis, they just stop working.

But even the most experienced riders can't real-time process all the visual information during a ride (although some like to think they can). Instead, our eyes and attention flit from one scene to the next in a constant state of building situational awareness and identifying threats. Riding in traffic isn't a holistic blanket of awareness – it's a series of focused moments building into a map of what's around you at any one given instant.

And it's more than just spatial awareness in the moment – our brains also have the ability to predict – and imagine – the future. We can predict trajectories (evaluating time/distance/speed equations to predict the path of other vehicles relative to ourselves) and predict likelihoods (will that car turn left or right, will that sheep run into the road etc). And we can also imagine futures that have no immediate sign of happening (will there be a tractor parked in the road around that blind corner?).

This all requires a lot of brain processing time and energy; riding in traffic is about as tiring as road riding gets.

Lesson Six: Make a mental model

Making mental models of the world can help us assume a level of control to things that seem uncontrollable or unpredictable. Traffic is the sum of multiple autonomous units, each interacting with each other and often consequentially. It's like Brownian motion; the random motion of particles as a result of collisions with surrounding particles.

On a large scale, traffic behaves with some of the characteristics of a fluid – for example, when it builds up before a constriction (to experience the full joy of this, join the A1 heading south a few miles down from the M62 junction during rush hour, where the road funnels from three lanes to two). It also moves in waves – someone dabs their brakes at 70mph on a busy motorway, and by the time the action has rippled back a few miles it's turned into a stationary traffic jam. And, like a fluid, traffic likes to fill gaps.

But sometimes it's better to also think of traffic as a herd of big, dumb animals, mostly following a herd instinct but with occasional stragglers wandering off and doing their own thing. Cows spring to mind, point being it's never a good idea to credit drivers with much intelligence; assume they're all capable of doing something stupid and unpredictable.

Lesson Seven: Always have an escape route

Be claustrophobic. Bikes like space around them, so a healthy riding goal is to be as far away from traffic as possible. This usually means getting ahead of it and pulling away (but sometimes it means slowing down slightly to let vehicles get away from us).

But no matter what the traffic density around us, we should always plan an escape route in every moment. If we're in a queue, filter to the front if we can – but if we can't, try and stop the bike with the front wheel pointing to a gap between vehicles, just in case we have to get out of the way in a hurry.

In flowing traffic, always have one eye – or an awareness – of where you can put the bike if something unpredictable suddenly happens in front. It's part of maintaining a good stopping distance, except in this case the space and time isn't for braking, it's to dodge, to move, to get out of the way and into safety.

Lesson Eight: Courtesy gets you killed

Vehicles flashing or slowing to allow other vehicles (or you) to pull out sounds civilised, but it's potentially dangerous for riders. Drivers – and riders – can sometimes be overly polite, leaving a gap for another vehicle to move into. There are lots of variations on the theme, but the best example is a line of traffic with a car waiting at a junction to pull across to the opposite lane. A polite driver leaves a gap and flashes the vehicle to pull out – unsighted, the rider overtaking the line of traffic arrives at the gap just as the driver is pulling out, and there's a collision. All because of courtesy. As a rider, you can easily spot this happening way before it does – beware of gaps in traffic, because it will likely be filled by a vehicle.

Lesson Nine: Dealing with heavy traffic

Like being in the wrong queue at the supermarket, drivers often switch lanes in heavy traffic, usually to move to a 'faster'-moving lane, or sometimes to make it across to an exit. Here's how to navigate it:

Filtering – filtering between stationary or slow-moving traffic is legal and explicitly permitted in the HC – however it puts some responsibility on the rider to 'take care' and keep 'speed low'. In cases of vehicles changing lanes or direction and knocking a rider off, courts can divide the percentage of blame between the rider and driver; speed is often a consideration in such cases.

Keep 'speed low' – we all like to make progress, but no point having it rudely interrupted by a collision. The slower we ride, the exponentially greater our chances of spotting vehicle movement before it's too late to react.

Cover the brakes, front and rear – cutting reaction time is key.

Sit upright – adopt an alert, 'active' riding position, and pump yourself up on the bike, head up, shoulders back. Taking on a 'fighting' physical stance psyches you up for quick, decisive reactions.

Concentrate – now is not the time to be thinking about what you're having for tea.

Be hyper-spatially aware – have your riding 'radar' switched on at full signal to the front and either side. See everything. Sometimes it feels almost like a sixth sense. But it also means knowing the width of your bike – where can it fit?

Control your bike – use everything: throttle, gearbox, clutch, both brakes, steering.

Own your personal space – be decisive, assertive and positive, but in balance: don't be aggressive or make exaggerated movements. But don't be passive, either! It's not quite controlled aggression; it's a level below a boxing match – more like gentle sparring with a hint of Zen thrown in.

Make a noise – some riders like to 'announce' their presence by holding a lower gear and keeping revs up – some even blip the throttle aggressively, which is a bit anti-social... but if it lets drivers know you're there...

Mind the gaps in traffic – vehicles tend not to change lanes when another vehicle is in the way – so if there's a gap, chances are there's someone looking to fill it. When filtering, always try to keep between vehicles on either side or gaps on either side. And if you see a gap in a lane up ahead, watch the car in the lane opposite as you approach – what's its 'body language'?

Vehicle 'body language' – are the wheels turned? Has the vehicle got even a hint of sideways momentum or direction movement? Has the vehicle's suspension 'set' changed? – milliseconds before a vehicle actually turns, its suspension will load up; sometimes you can actually see the body jack up before it steers. Some drivers make the tiniest steer in the opposite direction before changing lanes, unconsciously increasing momentum. Even spotting a driver turning their head in their mirror can signal an intention.

Lane hogging – lane hogging is probably the most frequently-seen example of bad driving, and probably the least harmful as far as riders are concerned. But it's a huge pain in the backside – lane discipline is notoriously poor in the UK. The biggest danger it poses to motorcyclists is frustration, which is a seriously unhealthy mental state on a bike. Take a deep breath, stay calm, don't take it personally, don't get angry. Sometimes it's tempting to drop to an inside lane and gently undertake the errant vehicle – if a solitary vehicle is sat at 65mph in the outside lane, it's entirely forgivable to simply slide past it at 70mph on the inside lane. And if you do, it's hard to believe a following police car would nick you rather than the stop the driver. Of course, sliding underneath at 100mph is a different matter...

Line of sight – in a line of traffic, always maintain a line of sight that lets you see well beyond the car in front – this usually means riding off-set to the vehicle, usually to the inside, and from a decent distance behind it. This is so you get more reaction time – if something happens up ahead, you'll see it early and you're not basing your reactions solely on the car in front. It also means you have an escape route – always, always, always have space to move into in an emergency.

Classic SMIDSY – sadly, very common and very deadly – and there are countless subtle variations, but it's basically a vehicle pulling out from a junction into a rider's path, or turning into a junction across a rider's path. Sometimes it's an open road and the driver isn't paying sufficient attention, sometimes it's at night, sometimes they see you but get the speed/distance/time calculation wrong, sometimes you're obscured by a larger vehicle and they assume there's nothing behind it. The result is almost always bad.

The name – Sorry Mate, I Didn't See You – is actually unhelpful; while the blame might be legally attributed to the driver, the responsibility has to be on the rider.