Where Do You Look? World’s First Eye-Tracking On A Bike

BikeSocial Road Tester. As one half of Front End Chatter, Britain’s longest-running biking podcast, Simon H admits in same way some people have a face for radio, he has a voice for writing.

19.12.2020

“Where we look is where we go,” they say. And good observation – spotting hazards, ‘reading’ the road, seeing the right line – is at the very core of fast, and safe, riding. It’s the key to unlocking every aspect of riding technique, and the key to building confidence. Nothing improves our safety and makes us smoother more efficiently than learning where to look, and what to look for. It’s a fundamental.

On the road, looking in the right place ‘buys’ us critical, precious time – time to react, time to plan. The sooner we spot a hazard or potential hazard, or the sooner we define what line the road is taking, the sooner and more accurately we can adjust our speed and/or position to deal with or adapt to it.

Even the smallest moment of time gained can help us. At 60mph we travel 88 feet in a second; or that’s the length of a car in 0.2 seconds – less time than it takes to blink. It can literally make the difference between continuing our ride without even realising we had a potential problem, or ruining our day in a very big way.

The principle of buying time by looking in the right place and at the right things is exactly the same as the way a pair of correctly-adjusted headlights lets us see as far as we can at night – and how if they’re badly adjusted, we can’t ride at the same pace because we can’t see far enough ahead. Riding and looking only at the patch of tarmac 20 feet in front of your wheels is like turning our lights off at night.

Lowering our eyes is a natural instinct, though, so we shouldn’t feel like a failure for doing it. On the one hand, riding a bike at speed is an entirely unnatural thing for a human brain and vision system to cope with – it hasn’t evolved to deal with being transported at high speeds. For most of human history, the fastest thing we had to deal with was a charging bison.

*this is not a bison

However, as it happens, bison actually charge at around 35mph – and so for a human standing in the way, being able to look into the distance and spot 800kgs of bone, flesh and hide hurtling towards them while it was still far enough away to be avoided, was a handy skill.

Thus humans got pretty good – in comparison with most other big mammals – at detecting movement in the far distance; it meant we could get out of the way of things moving towards us – but, more often, it also meant we could spot prey a long way off, and predict its movement. For humans as predators, long distance eyesight was an evolutionary necessity (we also used long distance visual acuity to gain advantage fighting each other, predictably).

However, the evolution of human vision also left us an unfortunate legacy when it comes to riding motorbikes. It’s fairly obvious that developing excellent near-sighted vision was important too – it’s all very well planning for something away off in the distance (and, therefore, the future), but in the here and now, with a sabre-tooth tiger lurking, camouflaged, in the hedge a few feet away, or if we’re about to step on a cobra basking in the sun, or if Boggo the caveman from the tribe next door is swinging a club at our head – then having eyes than can switch focus and help us deal with immediate threats is pretty useful.

But not so much on a motorbike. Our brains are hard-wired to draw our eyesight in for close-quarters survival or combat – and exactly the same thing happens today when we sense danger on the road. Our eyesight naturally drops lower, scanning our immediate surroundings and assessing the risk. It’s why we drop our eye line and look lower when we’re worried, stressed, tired or when we panic. It’s also a step on the path to target fixation – the moment when fight or flight stops making sense to our mammalian brain and it simply stops doing anything, like a rabbit in the headlights – and then we ride straight into the thing we wanted to avoid (there is an added subtlety to the phenomenon of target fixation: on a bike, the act of avoiding an obstruction often involves steering or machine control that superficially appears to put us in greater danger).

Where should we look?

Using a pair of eye-tracking glasses we look at the differences between a professional racer, a fast group track day rider and a novice track day rider before switching to the roads.

So in summary, our natural response to riding a motorbike on a country road is to focus, literally, on the danger under our noses – but the trick is to drag our perfectly-adapted eyes up to the horizon, and study that instead. Of course, it’s easier said than done – but knowing it’s what we’re supposed to do is the first step; then practising it, rehearsing it, doing it is the second, third, fourth step – and so on, for the rest of our riding careers.

So, where should we actually look? And how long do we look at it? Does a novice rider look in the same place an experienced rider does? Is there a difference in town and on the road? And where do different riders of different abilities look when they’re riding on track?

Bennetts BikeSocial is going to find out.

We’ve arranged to test, for the first time in the world, a pair of eye-tracking glasses while riding a motorbike.

Eye tracking is often used by companies who want to understand what shoppers look at when they’re scanning the shelves – which colours and logos catch the eye more than others, what shape of packaging is more attractive etc.

But we think this is the first time it’s ever been used to measure riders’ eyes while they ride.

The technology was once fairly bulky; but these days it’s been miniaturised into a simple pair of spectacles and a mobile phone.

We’re using Pupil Invisible eye-tracking glasses and software, developed by Pupil Labs in Germany. The glasses are made from a tough plastic composite and have two tiny cameras measuring the position and gaze of each eyeball set just inside the rims.

A conventional video camera clips magnetically onto the outside of the frames, on the side of the glasses. This records the forward view. The recordings are sent via a USB-C cable to a standard Android mobile phone running Pupil Lab’s own recording software. Once the wearer’s eyes are calibrated with the glasses, it’s simply a case of pressing record and riding.

When the video data has been collected, it’s uploaded to a Mac or PC, then run through Pupil Labs special software which uses complex algorithms to track the recorded eye movement and interpolate it with the forward-viewing video. The result is a moving crosshair overlaid on the recorded scene, effectively showing what we’re looking at and how long we look at it for.

As this is the first time – we know of – that riders have had their eye movement tracked, what we’ll find is unknown. We don’t even know if they’ll actually work!

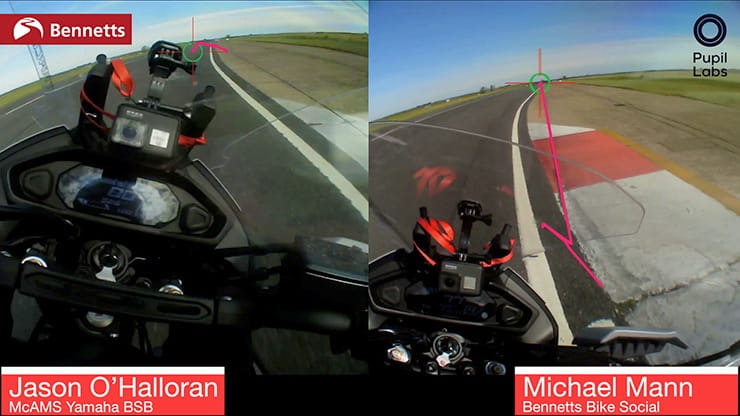

We’ve broken the tests into two sections: on track and on road. At the track we’ve enlisted the help of McAM’s Yamaha star Jason O’Hallaran (British Superbike winner and Championship runner-up in 2020), and BikeSocial’s own Michael Mann (experienced track day rider) and Chris Newble (novice track day rider).

We want to find out what three different levels of rider pace look at on track – and see if we can pick up any tips from them.

To create a control environment, we’ve come to Bedford Autodrome to use a circuit layout none of the riders have ridden before. We also using a standard mid-paced road bike, in Yamaha’s Tracer 700. The track is a fairly sterile environment in terms of distraction – we know where we’re supposed to be looking, which is through the corner and as far ahead as possible. The track conditions and direction are the same every lap, so all our attention should be on where we want to go.

Once we’ve kitted up and learned how to squeeze the Pupil Invisible glasses into everyone’s different lids – it’s a tight fit with the micro camera on the side of the lenses, and tricky getting the USB cable around the riders’ ears – it’s onto the testing.

Jason is up first. His day job is riding really, really fast, but – as you might expect – where he looks is a natural process and he’s never consciously thought about it.

“I’m not overly aware of it – it’s sort of sub-conscious. I’ve done it for so many years now, I just know where to look. In a race it changes a bit – depends on who’s ahead of you, or if you’re trying to make a pass. Normally when you’re on your own you’re looking a long way through the corner.”

Does he ever get distracted by stuff at the side of the circuit?

“Only on cool-down laps; after the race is finished. But not during it, no!”

BikeSocial’s Michael Mann is an experienced track day rider, riding in the advanced group. Does he ever think about what he looks at as he rides?

“I think the answer is ‘Yes I do’, but only because you’ve triggered a thought process! Definitely when I began riding on the road and the first time on track – there’s so much information going on, people telling you to do this, do that. It’s a bit overwhelming. But the more training you do, on road and on track, you then start to think much more about looking ahead and planning where you’re going; about the structure of a corner and how you pick your spot. So it comes with experience, and the more riding you do the further ahead you end up looking.”

Have you ever found yourself mid-corner thinking, ‘Hang on, I should be looking over there!

“Sometimes you’ll see something on the track or something will catch your eye and they’ll start darting around – you lose concentration and that’s when you’re prone to making a mistake or not run an optimum corner.”

BikeSocial’s Chris Newble is what can be called a track day novice.

“I usually win the novice group,” he jokes. “I enjoy track days, but I’m normally at tracks watching BSB and people like Jason. I’m pretty novice; I do more road riding than track days and in terms of where I look on the track, I know where I need to be looking but there so many other things that distract me; I’m looking all over the place really – there’s no clear direction. I’ve done a few track day schools and they tell you where you should be looking, but on the road I’m risk-averse so on track I end up looking at stuff I know I shouldn’t be.”

RESULTS - Chris Newble

Chris, as he predicted, is distracted by everything from fiddling with his visor, to a flock of birds, to trackside furniture. One of the things to think about before going out to ride on track is why we’re doing it. If we want a nice, easy, breezy ride around, that’s fine – we can look at whatever we like and think about whatever we like. But we won’t go much faster than we already do. If we find ourselves gazing at the clouds down the back straight, thinking about what’s for tea, then as long as we aren’t endangering anyone else, no worries.

But if we want to improve our riding and our pace, we need to focus mind – and eyes – on exactly that. Chris’ wandering eyes signify his mind and attention is also wandering.

Chris’ gaze is also constantly dropping from what’s far ahead – his braking points, corner entry and corner exits – to check what’s happening just in front of him. It’s a reassurance look; a confidence check, constantly updating on what’s about to go under the wheels, but in reality far too late to do anything about it.

Chris also constantly checks the clocks, looking at gear and speed. This is, again, a reassurance habit he doesn’t really need on track – the bike speed isn’t relevant. It’s why some track day riders tape over their clocks in an effort to stop themselves being distracted by them. Same goes for mirrors, although Chris isn’t bothered by his.

Chris also tends to look at braking makers, apexes and exits too late and for too long; he only picks up the last braking marker as he’s almost at it, then fixates on the apex until he’s at it, and only then looks up for the exit.

But as soon as he sees it, his eyes flick back, double-checking the apex is still under his wheels. This is wasted eye-time; the track hasn’t changed since he last looked. But it’s a classic reassurance look.

RESULTS - Michael Mann

Michael is an experienced track rider and has ridden with and picked up tips from some of the biggest names in British racing.

And immediately his eyes give away the difference with Chris – Michael is much more focussed on the track only, and the only furniture he gets distracted by is the right sort; braking markers (he actually brakes later than Jason!). His gaze is also slightly higher than Chris’; he spends more time looking further ahead.

But even Michael still spends a lot of time looking at the clocks; we all like to know how fast we’re going, but top speed on the straight isn’t the competition; lap times are. It’s wasted eye time and brain space.

Michael also looks for the apex early, then looks for the exit. But all through the corner his eyes are constantly flicking back and forth between the apex and the exit; it looks almost as if he’s using his eyes to constantly ‘describe’ the line he wants to take, drawing it out using his gaze.

This is a sign he’s not 100% committed to the corner – it’s a road-riding habit, and comes from checking the condition of the tarmac and double-checking road positioning; road riders tend to look at where they’re going in the far distance, then drop their eyes to the mid-near distance for a ‘comfort’ check, then back again, repeatedly. On the track, it’s unnecessary. Nothing has changed since the first look – or the previous lap, come to that.

RESULTS - Jason O’Hallaran

Jason’s eyes do exactly what you’d expect; they look as far ahead as they can, like Michael, then pick up the apex and exit at about the same time as Michael – sometimes even slightly later. But where Jason differs from a track day rider like Michael is he has no double-checking – his focus is only on one place; it never flicks back and forth. It’s fully committed after an initial look.

This steady gaze at the next objective gives Jason more time to work out his optimal speed and line; it’s trading reassurance for processing time. On the road – especially an unknown road with hidden hazards – this kind of commitment isn’t a great strategy for survival and if Jason used his eyes like this on a Sunday blast in the Yorkshire Dales, it’d be problematic. And it’s one reason why riding for leisure on the road is probably not a great idea for active professional racers – like the difference between being familiar with the grip offered by slicks, then getting used to conventional road tyres; it can take some time to re-adapt back to slicks again.

TRACK Conclusion

Eye-tracking has shown a couple of interesting things – things we might have already guessed, but it’s good to see them confirmed.

We know the key to successful track riding is to look as far ahead as we can, and use our focus on the exit to ‘draw’ the bike through the corner – again, we go where we look.

But it’s a surprise to see how committed Jason is; a long look at a corner – entry, apex and exit – gives him time to store up all the information he needs – speed, line, control points, exit – after which he moves on to looking for the next entry. It’s a one-stop approach, buying him time and brain space.

Michael is a road rider and brings the tools of road riding with him – his eyes are much more active, constantly checking and re-checking his line and speed – and looking at his clocks! This isn’t a problem – it’s a positive advantage on the road – but if he wants to get closer to Jason’s lap times, experimenting with fixing his eyes on the prize might help. As would taping over his clocks.

Chris is riding at a pace and level where he’s happily looking at whatever he likes – and that’s not a problem if he’s just enjoying riding on a track. He knows he shouldn’t be checking out trackside flowers and animals, but he’s okay with it. But if Chris is serious about speeding up, he’ll need to be more serious about what he looks at.

ON THE ROAD

As we know, the road is not a track. And its challenges are, for the eyes, far greater than a track – changeable road conditions, a wealth of roadside furniture, random hazards, traffic coming the other way, speed limits, mirrors – the sheer quantity of information thrown through the eyes and into the brain is astonishing; that we can cope at all is remarkable.

We’ve decided to find out what we look at using two riders in two environments: myself and BikeSocial’s Stephen Lamb, riding both on B-roads and on a busy city high street.

Steve and are both competent riders; through a life spent as a professional road tester, I have the edge on experience – but Steve has done more riding courses than I.

On the B-road section, which I know well and Stephen is much less familiar, it’s impressive how aware Stephen is of his surroundings, even to the point of using a fleeting gap in a hedge to scan for traffic around a blind corner. We both fix our gaze predominantly on the vanishing point (the converging point in a corner used to ‘trace’ the radius of the bend) and we both track our gaze backwards and forwards through the corner, re-establishing the line and checking the tarmac. My eye-line is slightly higher than Steve’s and rests a bit longer on the vanishing point because I know the road better.

The eye-tracking also shows I turn my head less than Steve – his observations are very deliberate, turning his head to check his mirrors; my head remains relatively still and I move my eyes to check mirrors and surroundings. This may be a throwback to Steve’s training, in which you need to demonstrate to observers you are actually looking at the things you’re supposed to be looking at; I’ve never cared what anyone else sees or doesn’t see, so it’s less effort to just use my eyes. It’s also quicker.

What is surprising about our B-road ride is how little we both appear to be looking directly at potential roadside hazards – unless it’s a car or a horse (Steve spends a lot of eye-movement looking when he has to creep past a horse on one section) or the occasional hard stare at farm turning, our eyes stay fairly fixed on either the horizon, line though a corner, in the mirrors or at the clocks. As neither of us are in the habit of running into problems, we must also be using our peripheral vision, probably checking for movement at the side. This is one reason why it’s good to occasionally test peripheral vision – you can get it tested by an optician, or experiment with reading number plates without looking directly at them.

In town, it’s the polar opposite of riding on the road – here, Steve and I basically watch everything, eyes constantly darting from side to side. There’s no need to check lines and speed is so low we can spend more time studying our immediate environment for hazards – and there are plenty.

But we still need to build in reaction time; so the sooner we can pick up problems, the better the chance of dealing with them. Every movement and every interaction – a lot of the brain work in town is interpretation of what we’re seeing, rather than the challenge of picking it up. And that’s an issue of experience; of reading the body language of vehicles, the fluid dynamics of traffic flow, and understanding the inclination of humans to do stupid obvious things as well as stupid random things.

But, as on the track, B-roads and in town – the fundamental use for our eyes is to, effectively, allow us to see into the future. They’re like a pair of crystal balls.

Because that’s the real key to survival – if we know what’s coming, we can be masters of our own destiny.

Share on social media: