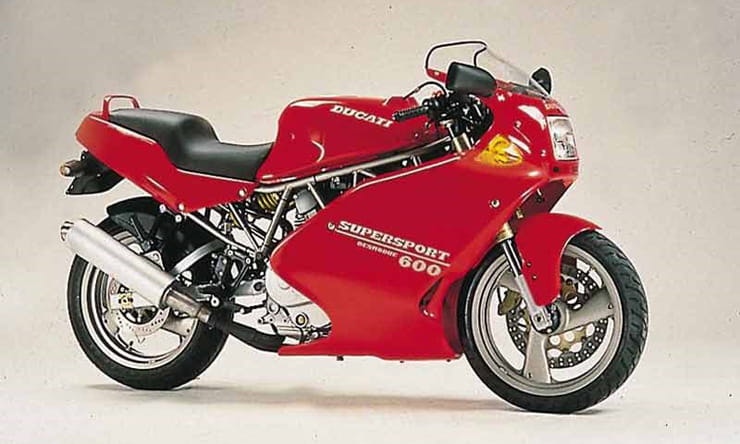

Ducati Supersports Range - Modern Classic Review & Buyers Guide

By Simon Hancocks

Motorcycle Journalist

12.02.2018

£1000 - £5000 | 53bhp – 84bhp | 585cc – 904cc ‘L-Twin’

In an age when sports bikes had long broken through the 100bhp barrier you could be forgiven for thinking that Ducati’s decision to drop an ageing two valve motor into an even more ageing frame design was a little strange. But back then, Ducati were a little strange.

The Ducati Supersport (or SS for short) range was launched in 1990 in 750cc and 900cc flavours. At this time Ducati were starting to get noticed for their WSB racers, but to most people were still a curiosity. The SS models had, almost nothing going for them on paper other than being beautiful, exclusive and Italian. Not especially quick, slow-steering, harshly suspended, uncomfortable and they fuelled as well as you’d expect from an ancient air-cooled motor fed by humungous carburettors.

Of course an owner (or the person trying to sell you one) will tell you that they have a soulful, torquey, charismatic power delivery in a stable chassis, with more character than any Japanese crotch rocket. And they are also right…sort of.

For a while this was ok – you paid not very much money and made your choice. The bikes got significantly better (and simultaneously worse) in 1998 when the engines got fuel injection and the styling went weird. Shortly afterwards, process of the original 900SS started to climb, putting them in that funny area of being more expensive than they deserved to be, but not quite collectable enough to be worth a look.

Thankfully, for anyone who wants the look, but not the expense, there’s a smart SS alternative. Maybe one of the 750s, which are still just about affordable or the almost forgotten 600SS, launched in 1994 and essentially a sleeved-down 750 that can be bought for a fraction of the price.

The engine is a 583cc, 90°, 2-valve ‘L-Twin’, so called because the front cylinder is almost parallel to the road and the rear cylinder almost vertical. The cams are belt driven and for a Ducati the engine is relatively solid. You have to keep on top of oil changes and use good quality stuff – Castrol Power 1 Semi-Synthetic 10W/40 is a good bet – but with regular changes the scary repair bills of some 90s Ducatis can be delayed if not avoided.

This is a classic engine that first saw use in Ducati’s Race bikes in the 70s in its earlier bevel-drive formation and then 80s when they switched to belt drive in larger configurations. The bikes were pounded round tracks like Imola and Monza in long distance endurance races, even competing at the TT and carrying Mike ‘The Bike’ Hailwood to a shock win at the Isle of Man in ’78.

Another feather in the cap of the 600ss is the frame. Not only does the steel trellis of the 600ss look just-so-right it again was developed on the track. The frame, brakes, geometry and suspension are all directly descended from the Ducati 750F1 race bike that Marco Lucchinelli took to victory at Daytona in 1986, for the most part they remain as per this machine.

Buying a 1990s Ducati is not without its risks though; the Italian firm went through many financial challenges in the 70s, 80s and 90s and not only did quality control suffer, but the components used on supposedly identical models could vary depending on which supplier was giving credit that month. Ducati was bought by Texas Pacific Group (TGP) in 1996 and the new parent company’s wealth and experience with mass production did had a significant effect on quality. Buying a later model doesn’t mean zero breakdowns, but the chances are reduced.

It’s ironic that Ducatis of the 80s and 90s were blighted by electrical problems given that the company started out making electrical items like radios but with thorough maintenance and a decent toolkit they can either avoided or fixed. The regulator rectifier is a well known weak spot due to its location. The bracket it is mounted to catches rainwater that runs off the fuel tank. Eventually this corrodes contacts or gets inside the unit. The ignition coils are also well known for breaking. If one of them goes buy two replacements as the other one won’t be far behind!

Luckily for anyone thinking of buying a 600ss (or any of the carb’d SS range) parts are plentiful and unlike later model Ducatis relatively cheap. Most of the SS range’s cycle and engine parts went on to create the bike that saved Ducati from collapse; the Monster. This bike’s success has meant that you can pretty much buy everything for the 600 even today 24 years after its launch. The bikes are also extremely easy to work on. The fairing sides come off in a couple of minutes and simple jobs that would require the engine dropping out of an across the frame four can be completed with the engine in thanks to the unrestricted side access.

If you’re looking at a second hand one, it’s imperative to get a test ride. Check the engine is cold when you get there, if not, keep them talking till it is! A well set up bike should start with a touch of choke and tick over at about 1100rpm. Don’t worry about that banging noise on tick-over it’s probably not the big end – the L-Twin models all suffer from piston slap which is accentuated on the air-cooled faired bikes. When the engine starts a bit of smoke isn’t a bad thing but if that doesn’t stop when the engine warms up it could spell trouble. Take out the oil filler cap and have a look inside, you don’t want to see any milky colouration or a ‘mayonnaise’ type build up from moisture in the oil.

The 600ss has no adjustment on the front forks so give them a good check rocking the bike on the front brake. If the bike bottoms out over speed bumps when you test drive it the fork springs might need replacing – sometimes caused by a bike sitting on a paddock stand for a few years. It’s also worth changing the fork oil because, chances are, it’s never been done. Another part of the bike that doesn’t fair well to sitting in the garage are the belts. The radius of the top pulley is so small that over time the belts can weaken and crack leading to a terminal engine failure. If you are storing a 600SS (over winter for example) put it in gear every now and then and move it back and forth so the belts don’t sit in the same spot.

The rear shock has preload and rebound adjustment and is well protected from any road dirt and grime thanks to the 600’s massive hugger that envelops the rear wheel. As with the front, sit on the bike and bounce it up and down, it’s a fairly stiff shock on standard settings but should return smoothly and without any bouncing.

These bikes are mechanically simple and with such good access many owners will attempt to service and fix the bike themselves so a full history is less common than on the water-cooled 916 series.

When new, the baby SS got a kicking in the bike press for being considerably slower than any Japanese 600 (or even the 400s of the day), but that’s missing the point. This is a bike for people wanting something other than performance. Once you get the point, a Ducati 600ss is a hoot to ride. Its got so little power in such a well sorted frame you can ride it on the throttle stop everywhere. The brakes are Brembo Goldline discs and calipers and although you only have one on the 600 they do a great job – I’ve ridden mine as hard as I could on some fast roads with hard braking points and never once suffered from any brake fade. If you want to get a foot on the ladder in the world of Ducati ownership but don’t want to sell your first born child, the 600ss is a great starting point.

Ducati Supersport Technical Specification

600ss 750ss 900ss