Honda VTR1000 FireStorm: 20th Anniversary Owners’ Meet

BikeSocial Road Tester

09.08.2017

This isn’t quite the start to the 20th anniversary meet-up of the Honda VTR1000 FireStorm owners’ Facebook group BikeSocial was expecting – we’re photographing a yellow VTR when a red FireStorm pulls up and stops just behind it, bang in the way.

“Oh, mate, sorry – can you just roll your bike back a bit please?”

The red bike’s rider looks across, from 20 feet away, through a misted-up visor. “No,” he says, flatly.

I look up from behind the camera, and raise an eyebrow. “Seriously?”

“Seriously, f**k off.”

We’re gathered in the car park of the National Motorcycle Museum near Solihull, where some 30 or so Honda VTR1000 FireStorms are getting together from all over the country – and one has even crossed the sea from Holland, and another from Spain – to celebrate two decades of the 90° V-twin. But it’s a damp, overcast morning, which probably isn’t helping lift the mood. It turns out the helpful red VTR rider, called Mac, is actually the event organiser – he’s just ridden a couple of hundred miles from north Kent in the rain, which might explain his reluctance to dick about.

“No worries, I’ll just move the other bike 10 feet back instead,” I say, resisting the temptation to clear off and leave them to it. Calm before the FireStorm, and all that.

Launched in the same year as Suzuki’s TL1000S, Honda’s 996cc 90° V-twin is, like the Suzuki, a half-faired, road-based sportsbike that stops some way short of being a full race replica. In a softer state of tune and with a less committed riding position than its Japanese rival, the 110bhp VTR features a few firsts for Honda, and one last; it debuted their late 1990s fashion for using engines as fully stressed members, doing away with the frame’s side plates and mounting the swingarm pivot directly to the rear of the crankcases (as would the later VFR800i and 929 and 954 FireBlades). The VTR also features nutless con-rods, side-mounted radiators, the (then) largest-ever intake valves on a Honda road bike. But its pair of massive 48mm throttle bodies are Honda’s last-ever to be fed by carbs.

Performance-wise, the VTR does 152mph, averages 35mpg (but with a 16-litre tank, fuel range is limited to just over 100 miles), weighs 205kg fully fuelled and, in 1997, cost £7995 (nearly £14,000 in today’s money; same as the TL1000S and nearly five grand less than Ducati’s 916).

And, somewhat unexpectedly for Honda, the VTR was a big hit; less intimidating than the TL1000S and untainted by reports of instability, the FireStorm proved popular with riders coming back into biking after a few years – the so-called ‘Born Again Biker’ boom – who wanted a sporty, reliable bike with the V-twin cachet of a Ducati 916 but without the initial costs, the running costs, the extreme sportiness or concerns over durability. Honda’s reliability, earned over the previous decade, made it an easy, obvious choice. The VTR’s manageable ergonomics, sleek, uncomplicated looks and smooth motor also ensured popularity with lady bikers.

The first design was so right (dicky camchain tensioner aside), there were only ever minor updates; in 2001 the VTR got a bigger 19 litre tank, minor suspension mods to uprate what was a fairly soft and rudimentary ride, an updated LCD dash and a refined, more upright riding position. The 996cc VTR engine was only ever used in one other model – the XL1000V Varadero adventure bike – and the FireStorm shared few components with the later, much sportier, SP-1 and SP-2. Global VTR production ran until 2005.

In the late 1990s you could hardly move at bike meets for VTR1000s – but by the mid-2000s Britain’s biking appetite had shifted to 600cc and 1000cc sportsbikes, adventure bikes, and sporty naked roadsters. The VTR suffered the fate of many once-ubiquitous bikes that drop out of fashion – values were seriously depressed and many FireStorms changed hands repeatedly, each time acquiring a new patina of decay and neglect, and losing a few hundred quid as new owners paid less attention to them. Right now you can pick up a scruffy, badly modified VTR1000 for around £1000 or less, while a mint stocker should still be well south of £2500. Compare that to the price of Suzuki’s TL1000S and TL1000R, both of which sold fewer but now command higher prices – and don’t even think about looking at what people are asking for SP-1s and SP-2s!

But it may yet happen to the VTR. As the generation of thirty-something riders who cut their big-bike teeth on the VTR 20 years ago move into their mid-50s, their thoughts will turn once more to Honda’s V-twin – and that’s why values for well-maintained standard FireStorms could well start to creep up over the next few years.

Meanwhile, back at the VTR1000 FireStorm owners’ Facebook group meeting at the National Motorcycle Museum, the frosty reception has thawed – and the rain has stopped – as over 30 VTRs line up obligingly in car park for a group photo. They start their engines and the cacophonous barrage of more than 60 98mm pistons pumping up and down in 498cc cylinders, venting to atmosphere alternately every 270° and 450°, is like an aural D-Day. You can almost see the air moving. When they’ve all stopped, BikeSocial selects a few of the most interesting bikes and chats to the owners...

Martin Veck’s VTR1000

“I first got a VTR when I came back to biking after ten years away, in 2010. And it was cheap; the cheapest thing you could buy, performance-wise, for the money. About three weeks after that I wrote it off and had a trip to hospital, when a van did a U-turn in front of me. So I had another couple of years off, then I bought another one.

“Everyone said they were the boring V-twin when they came out – you know, compared to the TL1000S and the Ducati 916. But as the years have gone by, people realised what a good roadbike they still are. And they’re comfortable too – I used to have an SP-1 and I had to go see a chiropractor after every ride. Great for the track no doubt, but this is better for the road.

“I love the character of the VTR; the V-twin torque; and it’s very addictive. And if they’re ridden well they can hold their own today. Plus, you get a lot of bike for your money – I could buy a new bike tomorrow if I wanted but I loved the FireStorm as soon as I rode it. It’s stayed with me ever since; this is my third. I’ve modified them all, but not as much as this one. I wanted to keep it looking standard.”

Martin’s VTR spec

Engine: stock with Akrapovic full system, Ade Whitmarsh manual camchain tensioner

Chassis: Marvic cast magnesium wheels, Michelin Pilot Power 2CT tyres, PFM cast iron discs, 6-pot calipers, Brembo radial master cylinder, Roger Ditchfield revalved forks, Öhlins steering damper, Öhlins shock, R&G bars ends, Baglux tank cover, touring screen, mirror extenders, peg lowering kit, Givi monorail, Oberon filler cap, Goodridge hoses

Mac’s VTR1000

“I bought my first VTR in 2006 – I’d just moved house, and had an NX650 Dominator and it was crap for commuting. So I was looking for a 600 or maybe a Yamaha TRX850. But the I saw a VTR for sale, bought it, doubled the mileage in a year just commuting.

“I hated it at first. I was at work and I went down to the shop and picked it up during my lunch break. I pulled away from the shop and soon as I closed the throttle it went ‘Bleeeeeuuurgh...’ – but you get used to it and I love them now.

“In 2013 I had a 30mph rear end; broke my wrist and elbow, and wrote the bike off. So I bought another one while I was convalescing for seven months, but that one turned out to be a bit moody – it was a French bike but had a mph speedo. So I wasn’t sure about it, I sold it to someone else. Then I bought this one; the red bike; at the end of 2013. I use it for all the VTR meets we have – and since then I’ve bought more FireStorms; I’ve got three more in the garage, and I’ve bought and sold another two. One of them is here.

“The main thing about the VTR is the torque. It’s all about the torque. It’s forgiving, easy to ride, you can filter easily and it’s great in traffic. With a 70-mile commute it’s ideal. I like the build quality too – there are a few issues with corrosion, the shock linkages seize, things like that. They’re of an age where they need a bit of loving now.”

Mac’s VTR spec

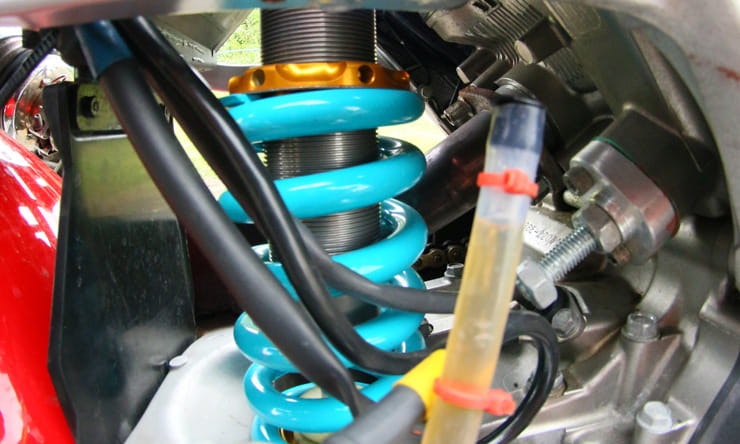

Engine: stock with Moriwaki titanium full system

Chassis: Michelin Pilot Road 3 tyres, Armstrong wavy discs with Brembo 4-pot calipers and adapter bracket, Goodridge hoses, quick-action RC45 throttle, Roger Ditchfield revalved forks, YSS rear shock, suede-covered seat.

Alan Cheadle’s VTR1000

“I bought this bike, my first VTR, two years ago. It wasn’t this colour then – it’s had loads chucked at it. I bought it because I wanted a change – I’d had across-the-frame fours more or less all my life. My last bike before this was a CBR1000F, and I just wanted something a bit lighter, that I could push around. I’d never had a V-twin before, so I thought I’d try one.

“I hated it at first. It felt horrible. The engine felt harsh; it was a culture shock. With the sound coming up from under the tank it sounded like a bombing raid over Dresden. But within 50 miles I loved it and now I can’t make enough noise with it!

“I started modifying it because I want it to be different. It’s a case of seeing something you think will look good, and buying it.”

Alan’s VTR spec

Engine: stock with JCE exhaust system

Chassis: Michelin Pilot Road 4 tyres, Skidmarx carbon hugger, Hyperpro fork springs, Hyperpro shock spring, WizBiz wavy discs, SBS pads, stainless rad covers, carbon wrap mirrors, carbon frame protectors, titanium bolt kit, polished swing arm, paint by Mick Wright at Camden Garage Racepaints, Derby.

Ian Mercer’s Moriwaki VTR1000s

“These are bikes were built by Roger Ditchfield, of Revolution UK. He built all the UK Moriwaki bikes, road and race. The bike on the left is an ex-Honda Britain bike, that Roger’s son Mark bought and raced as a Stage 2 tuned bike, at about 150bhp. It’s got a lot of Spondon in the chassis – frame plates, swingarm, yokes.

“The bike on the right is the Stage 3, making around 170bhp originally, but now nearer 155bhp, with a Moriwaki-modified frame and swingarm. It’s a bit more rigid than the other bike. In fact it’s a handful; the bikes are chalk and cheese to ride. The Spondon bike is beautiful – the riding position, the handling, I just get on better with it.

“I bought a bog standard VTR in 1999. I loved it, and I wanted to do it up, but money was tight. I bought an exhaust from Roger, then a couple of years later a Stage 1 Moriwaki 50th Anniversary bike came along, that Roger had done. It had everything a road bike could have – it cost the guy £25 grand. I parked up my standard bike and started using the Anniversary bike.

“Then I got wind of the ex-Honda Britain bike was up for sale – the bloke had both these bikes, but it was the one on the left I really wanted. So I bought it. And then a few years later the same bloke sold me the other bike too. So I’ve got all four now – stock, a Stage 1, 2 and 3. The full set.”

Ian’s Moriwaki VTR specs

Engines: Moriwaki Stage 2 (left) and Stage 3 (right). Stage 2 is hi-comp pistons, gasflowed and ported head, engine blueprint, airbox mods. Stage 3 is the full Moriwaki race spec with the above plus Moriwaki cams, rods and pistons

Chassis: (left) ex-Honda Britain with Spondon modified frame, Spondon swingarm and yokes, (right) ex-Moriwaki race bike with Moriwaki braced swingarm. 1999 FireBlade forks with Roger Ditchfield internals, Penske shock, AP Racing cast iron discs and 6-pot calipers (both bikes).

Moriwaki VTR1000 Firestorm

In the 1960s Mamoru Moriwaki started out as a racer in a Japanese domestic series, riding for the legendary tuner Pops Yoshimura. During his time with Pops, he taught himself mechanical engineering and learned how to tune engines – and also married Yoshimura’s daughter.

Come the 1970s, Moriwaki had set up his own company using aluminium as a frame material, and was tuning big Kawasaki motors. Riders like Graeme Crosby, Dave Aldana and Wayne Gardner raced in Moriwaki colours in the 1970s and 1980s, beating factory teams in the Suzuka 8hr and in Australian national races, over here and in the US. In the 1990s Moriwaki became associated with Honda, running a VTR1000 Firestorm at the 1997 Suzuki 8hr. Moriwaki claimed the bike was making around 145bhp, using high-lift cams, head work, valves, high compression pistons and his intake, exhaust and carb tricks. Rods and crank were stock: “Very strong metal,” said Moriwaki-san himself. The well-braced frame and swingarm ran Nissin brakes and Moriwaki’s own forks and shock linkages. Electrical problems put the bike out of contention, and it came home a few places behind a team running a Ducati 916. In 1998 Moriwaki brought the bike to the UK, and Jim Moodie raced it at Donington. Through his connections with the family, Roger Ditchfield’s Revolution Racing took up the name in the UK, and Roger’s son Mark raced a Stage 3 Moriwaki VTR1000 in the 1999 National Superstocks season (now Ian Mercer’s bike, left, above).

Meanwhile, Moriwaki in Japan continued to develop race technology, running an RCV213V in MotoGP between 2003 and 2005 with a steel tube Moriwaki frame (and the aluminium frame and yokes of the RC213V-S road bike are actually manufactured by Moriwaki). A Moriwaki-framed Moto2 CBR600 won the debut world title in 2010 with Toni Elias.

Roger Ditchfeld, Moriwaki and VTR1000 road and race tuner

“In the 1990s Honda had been developing the SP V-twin for some time, to compete in World Superbikes. But they kept blowing crankcases apart so it needed a complete re-think. But rather than waste four years of development, Honda decided to stick carbs on the motor, make it a road bike, get it out and get some cash back in. They never expected it to be as popular and successful as it turned out – and then, obviously, all the development swapped back onto the SP.

“I believe that’s why the VTR is so easy to get improvements from with tuning. Because originally, it was designed for a higher-spec performance. I have never tuned an engine with so much potential for performance increase. It’s unbelievable really – to go from just over 100bhp in stock form to over 150bhp – that’s a ridiculous increase, but it was there to be had. You couldn’t possibly do that these days.

“What Honda did in those days was have the main HRC development in Japan, but also took feedback from national satellite companies. So in Japan they had Moriwaki, in the US there was Big Valley Honda, and I was doing Europe at that point. We got special parts to test, some of which had to go back to Japan; Honda would pool all that information – and that was for both the VTR and the SP. I’d no real history with Honda, but I’d known Mamoru Moriwaki for years, from when he first came over to the UK. So I got involved through those connections.

“All the other manufacturers in Japan start off with various teams all working on the one project, and inter-related from day one. Honda don’t work like that. They say to their engine designers, ‘Design us a V-twin’ and to the frame developers they say, “Develop us a frame for a V-twin.’ And they stay apart for a long, long time. You could see that being a problem, but Hodna don’t believe that it is. They believe the engine builder will build the very best engine he can and the frame builder is doing the same. Now there’ll be a cross-over area, but they think they’re getting the best from each team because they’ve not had limitations put on them early in development, with guys saying, ‘Oh, you can’t do that.’ They’ve always had that unique way of working, bringing things together at the start of physical testing.”

Share on social media: