What’s the future of motorcycle transmissions?

By Ben Purvis

Motorcycle Journalist

21.06.2024

Two production Honda semi-auto transmissions and BMW’s upcoming rival system: self-shifters are in the ascendancy

Logic says there should be an unbridgeable chasm between motorcycling and the automatic transmission. The former is all about the human-mechanical connection between a bike and its rider while the latter is all about labour-saving convenience and masking the deficiencies of the user’s own skills. But it’s looking increasingly likely that the unthinkable could happen: the automatic transmission could become dominant in motorcycling.

We all know that the motorcycle industry moves in a herd. As soon as a new technology hits a tipping point where its appeal to buyers overtakes the costs of developing and applying it, suddenly it appears everywhere. We’ve seen it with traction control, with selectable riding modes, with colour TFT dashboards and the phone connectivity they bring (another feature that seems at odds with motorcycling and its ethos of escaping from the daily stresses of life). All of these things were rarities just a handful of years ago, but ubiquitous today. Now engineers and motorcycle companies are turning their attentions to semi-automatic transmissions – a field that’s been barren for decades despite various attempts to farm interest in the idea but has suddenly become a fertile ground that manufacturers are hoping to harvest.

Semi-auto KTM 1390 Super Adventure will launch in September this year

BMW and KTM are the latest to get in on the action. BMW has announced the Automated Shift Assistant (ASA) system that will be an option on as-yet-unconfirmed production models in 2025. The terminology is carefully chosen, it’s automated rather than automatic, and it’s an assistant – suggesting you, the rider, are still in control. But the reality is that it has a fully-automatic mode as well as a pushbutton-operated manual setting, and BMW has developed it because there’s a genuine demand for such systems.

KTM’s own system will hit showrooms around the same time, debuting on next year’s new 1390 Super Adventure. The company’s own system, dubbed AMT (Automated Manual Transmission), again carefully maintains ties to our beloved manual shifts, but there’s no clutch lever. You can use bar-mounted triggers or a foot-operated pedal to swap cogs, but again the actual changes are made by an electro-mechanical actuator rather than muscle power and a switchable fully-automatic mode is expected.

Honda already has a 15-year head-start thanks to its dogged determination to bring auto boxes to the mainstream, and this year brings a much cheaper halfway house version, the E-Clutch, to showrooms on the CB650R and CBR650R, with more models expected to adopt the system in future. Yamaha already has experience with its own semi-auto, the YCC-S (Yamaha Chip Controlled Shifter) that was offered on the FJR1300 from 2006 until it was dropped from Europe a few years ago. It’s still available in North America, and there’s evidence that Yamaha is developing a new version of the system to offer on a wider range of more affordable bikes in response to the Honda E-Clutch – recent patent applications show it fitted to the MT-07 and R7, for example.

Even the emerging motorcycle industry in China is getting in on the game. CFMoto has recently been developing a semi-auto transmission to be fitted to the 700CL-X’s parallel twin engine, and QJMotor – Benelli’s sister brand – has also been working on its own similar system. Most recently a complete newcomer to the motorcycle scene, Great Wall Motors, has launched an eight-cylinder touring bike with an eight-speed dual-clutch transmission specifically to get one over on Honda’s six-cylinder Gold Wing, which has a seven-speed DCT.

This is how Honda introduced its DCT transmission to the world 15 years ago

Why the sudden interest? These companies aren’t turning to automatics simply because they can – it’s a convergence of affordable technology and growing customer demand that’s set them on the course of developing self-shifting boxes. They also understand that while grizzled old riders might be unwilling to surrender their traditional clutch levers and foot shifters, clutch and gearbox control is one of the steepest learning curves for new riders and the ability to eliminate that barrier could usher in customers that wouldn’t otherwise be able to operate their products.

Current systems

Evidence that the there’s demand for automatic bikes isn’t hard to find. At the low end of the market, automatics have been the norm since WW2 in the form of the continuously variable transmissions on twist-and-go scooters – dominating in a field where ease-of-use trumps riding pleasure at every turn. When it comes to big bikes, Honda, thanks to its 15-year crusade to popularise the sophisticated, expensive and heavy dual clutch transmission – which debuted in 2009 on the VFR1200F but can now be had on a broad array of bikes from the Gold Wing to the X-ADV – has done the legwork to both cultivate a market and show its potential.

Semi-auto Africa Twins now outsell the manual versions

Since the VFR1200F appeared in 2009, Honda has sold more than 240,000 DCT-equipped bikes in Europe alone. With each of them carrying around a £1000 premium over their manual equivalents, that’s quarter of a billion pounds-worth of business, and it’s growing fast. In 2023 the Africa Twin was Honda’s best-selling European model and it was the DCT-equipped versions that outsold the manual ones overall. For the standard Africa Twin, DCT bikes accounted for 49% of sales, while the pricier Adventure Sports version saw that figure rise to a remarkable 71%. Given the choice, more customers picked DCT than a normal gearbox.

We can get a more granular look at the UK market thanks to detailed breakdowns of new bike registrations every three months. Even though the UK tends to be a more traditionalist market than others, they show that since the CRF1100 Africa Twin replaced the CRF1000 version in 2020, 1217 DCT-equipped models have found customers compared to 1700 manuals. That’s about 42% DCT against 58% manuals, and even if we go back to the previous CRF1000 generation, there was a similar split, right back to the bike’s launch.

It's a similar story with the Honda NC750X, offered in both DCT and six-speed manual forms since its launch. Overall, since the model’s launch, more than 45% have been DCT bikes. But look at 2024 alone and the numbers skew in favour of the auto, with DCT versions accounting for more than 56% of UK NC750X registrations.

Elsewhere in the Honda range, the DCT version of the Gold Wing and Gold Wing Tour models completely annihilate the sales of their manual-transmission alternatives – more than 71% of UK registrations have been the DCTs, while the figures for other models like the NT1100 and CLX1100 show that buyers are pretty evenly split between the two gearbox options.

Twin clutches are key to Honda’s DCT advantage

Given the huge popularity of Honda’s DCT, particularly in the context of the large price tag that it carries on most models where it’s an option and the fact that it brings a not-insubstantial weight penalty of around 11kg compared to a normal manual box, is remarkable. And it’s even more remarkable that it’s taken so long for rivals to jump in with their own competitors.

The reason for the apparent delay is that the Honda DCT gearbox is a complicated thing, and Honda holds several patents in regard to elements of its design. The complexity includes two separate clutches, a completely different set of gearbox internals compared to a manual, and a control system that combines both hydraulics and electronics. It all needs to be overseen by a purpose-made computer unit that makes sure the shifts happen smoothly and at the right moment.

The payoff for Honda is that DCT is a genuinely seamless transmission – the twin clutches mean there’s no need to interrupt drive during upshifts or downshifts – and it can be operated in either fully-auto or semi-auto modes depending on the rider’s whim. At its launch in 2009 it was a remarkable technological achievement.

Twin clutches are key to Honda’s DCT advantage

What’s changed now is that other technologies have caught up, allowing much cheaper, simpler alternatives to create a semi- or fully-automatic transmission without the need for a clean-sheet redesign of a conventional manual or to expensively re-tool factories to produce a different transmission.

This can be seen in the recent explosion of popularity of the up-and-down quickshifter. A pure race bike tech just a handful of years ago, quickshifters that allow clutchless gearchanges once on the move are now becoming the norm across a huge array of bikes. The fact that all modern bikes now have ride-by-wire throttles – one of the technologies that has also led to the sudden spread of traction control systems – means that adding an up/down quickshifter is no longer a big deal. The ride-by-wire can already modulate the power or blip the throttle when commanded by the computer, so all that’s needed is a load sensor to measure when you’re pushing on the shift lever, plus a bit of programming of the engine management. It’s easy to see why bike companies are offering quickshifters on ever more models as a low-cost way to attract more customers.

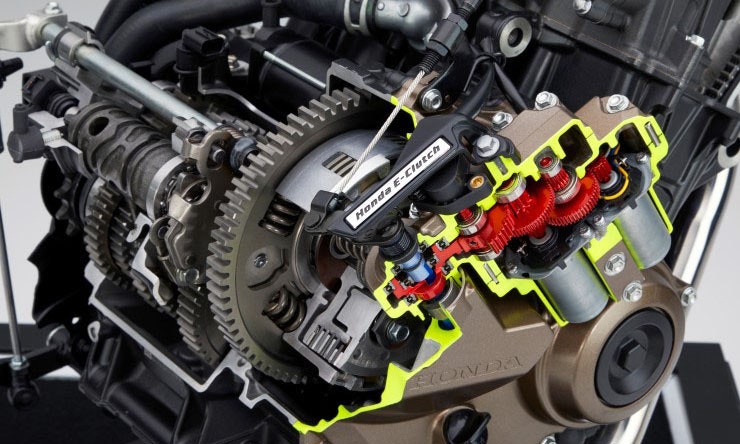

From there it’s a relatively small step to automate the clutch as well, allowing riders to start and stop without needing to pull in the lever. It can be done in a simple, all-mechanical way, like on MV Agusta’s SCS bikes, which use an aftermarket Rekluse centrifugal clutch allied to a quickshifter to approximate a semi-auto box, or by using more advanced, electronically-controlled systems like Honda’s new E-Clutch.

Honda E-Clutch is already available on the CB650R and CBR650R – more models will follow

The E-Clutch might have only just reached dealers on the CB650R and CBR650R but it’s something Honda and its rivals will be watching with interest. Unlike the heavy, complicated and expensive DCT gearbox, the E-Clutch adds just 2kg and around £100 to the price of the bikes it’s offered on. There’s no auto option, as the mechanical foot-operated shifter is still used, but it eliminates the need to use the clutch lever at all (while cleverly still keeping the lever in case riders want to use it, or as a backup if the electronics fail). It’s hard to imagine many customers not ticking that option, as it offers the best of both worlds for a minimal outlay.

BMW’s ASA system, which is expected to debut later this year when the company launches the R1300GS Adventure, but also to be available on other models in the company’s range in 2025, is a little more complex but also more capable. It uses electro-mechanical actuators for both the clutch and the gearshift, allowing it to work in either a fully-automatic or semi-automatic mode. In semi-auto setting, a conventional-looking shifter lets you pick the gear, but it could just as easily be a button on the bars as there’s no mechanical link to the selector drum.

ASA may not have the true seamless-shifting ability of DCT, but with the right programming it’s likely that riders won’t really notice much difference.

KTM demonstrated its next-gen 1390 Super Adventure prototype – with a semi-auto box – at the Erzbergrodeo this year

Other new systems in the works

The BMW ASA system bears some distinct similarities in its method of operation to a much older design – Yamaha’s YCC-S. Launched on the 2006 FJR1300 tourer, YCC-S also uses electro-mechanical actuators for the clutch and shifter, with a dedicated ECU to oversee the system, allowing gearshifts to be made by either push buttons on the bars or a foot-operated controller. It’s been in production for 18 years but has yet to spread to other models – something that now looks likely to finally happen.

Yamaha has filed new patent applications showing a similar semi-auto transmission system fitted to an MT-07 and an R7 – and it’s surely no accident that those bikes are direct rivals to the Honda CB650R and CBR650R that get the E-Clutch option this year. Unlike the Honda, the Yamaha design eliminate the clutch lever and the foot shifter, replacing them with bar-mounted push buttons that operate a computer-controlled gearshift. Although more complex than the E-Clutch and lacking the ability to revert to conventional, manual usage, it’s a design that opens the door to having multiple modes, including a fully-auto setting, to approximate the more advanced Honda DCT’s abilities.

CFMoto has also applied for patents on its own, similar system, again fitted on a bike in the same mid-sized market – the 700CL-X. The Chinese brand’s setup is quite similar to the Yamaha and BMW systems, with servo-operated clutch and shifter to allow complete computer control. Its differences, which the company hopes to be able to patent, relate to specifics of how the electric motor controlling the gearshift is connected to the shift drum inside the transmission.

Yet another company working on a twist on the same idea is Qianjiang, parent to Benelli. It’s filed patents for a clutch-by-wire system that, like Honda’s E-Clutch, retains the bar-mounted lever but allows the option of automatic operation. Fitted to the company’s own 700cc parallel twin engine, the system eliminates the mechanical connection between the clutch lever and the clutch – unlike Honda’s E-Clutch, which keeps it – and uses an ECU to translate the rider’s commands to the clutch. At its simplest, it can simply make it impossible to stall the bike or to make a ham-fisted shift by stepping in to smooth out the clutch operation and harmonise it with the electronic, ride-by-wire throttles. However, it could also be programmed to operate in a semi-auto mode, like the Honda E-Clutch, to eliminate the need to use the lever at all. I could even combine with an actuator on the gear shifter to allow a fully-auto or button-shifted setup.

CFMoto patent shows affordable Chinese bikes are about to go semi-auto, too

Success after decades of failure

The path to the sales success of the Honda DCT system – and the avalanche of copycats that it’s now about to bring – hasn’t been an easy one. There have been plenty of abject failures when it comes to automating motorcycle gear shifts.

The earliest, however, was pretty much an unqualified success. Shortly before the outbreak of WW2, American firm Salsbury (owned by aircraft builder Northrop) launched the first scooter to use a belt-operated CVT transmission, and once hostilities came to an end manufactures in Japan and Italy leapt on the same technology for low-cost transport needed for their war-battered populations. The CVT is still the normal twist-and-go transmission for scooters to this day, offering unparallelled ease of use that makes them so easy to adopt.

Attempts to translate that easy-riding, clutchless control to larger bikes have been fraught with difficulties, though.

Car-style automatic gearboxes, which work completely differently to manual transmissions that are the bases for all modern semi-auto bikes, have never really managed to get a foothold on two wheels. Honda’s Hondamatic CB750, offered in the 1970s, came close, using a torque-converter rather than a clutch and allying it to a two-speed planetary transmission. You manually shift between ‘low’ and ‘high’ and the torque converter provides the flexibility within those ranges. Although briefly popular, it didn’t remain so.

We’ve also seen attempts to bring belt-based, scooter-style CVT to larger bikes, for instance the Aprilia Mana. The Mana combined its 76hp, 839cc V-twin engine with a CVT featuring three riding modes back in 2007. It actually worked fairly well, able to operate either as a scooter-style CVT where the revs are weirdly disconnected from road speed or to be switched into a faux-semi-auto setting, with seven preset ‘ratios’ that it can shift between. It was arguably ahead of its time – perhaps if it had been launched today as a rival to the E-Clutch Hondas, a modern Mana might have been successful, but in the noughties it seemed to be answering a question that nobody had asked.

While the Honda DCT has been the breakout success of auto bikes, the company is also responsible for one of the most remarkable failures – the DN-01. Developed at the same time as DCT, the DN-01 featured an even more advanced drive system that used hydraulics to both change ratio and to take power to the rear wheel. A variable-displacement axial hydraulic pump was attached to the engine and pushed fluid to a hydraulic drive unit at the rear wheel, eliminating the need for a gearbox or a shaft or chain drive. Gear ratios were changed by moving a tilting swashplate inside the hydraulic pump, altering the stroke of several small pistons mounted in a circle inside the pump. When the swashplate was parallel to the pump, the pistons didn’t move at all, so pushed no hydraulic fluid through the system, but as the angled increased, so did their stroke, increasing the amount of fluid being pumped to the hydraulic motor at the back wheel. Great idea, but it was wrapped in one of the weirdest-looking bikes Honda’s ever made, lacked power (61hp was claimed from a 680cc V-twin based on the old Transalp motor) and cost a small fortune, so sales were miniscule and the DN-01, launched in 2007, was gone by 2010. It did, however, inspire the NC700 and NC750 ranges – complete with DCT transmission option – that would follow it.

Honda’s path to semi-auto success wasn’t an easy one – the DN-01 was a notable misstep

So, is the manual gearbox doomed?

It’s clear that semi-auto and fully-auto bikes have the potential to pinch plenty of sales from conventional manual designs. It might be tempting, then, to look towards the car market where a similar thing has happened and manual transmissions are rapidly disappearing as a result.

While automatics have dominated in some markets for decades – they’ve been dominant in the USA since the 1950s, for example, and manual cars over there account for less than 1% of all sales now – they’ve only recently started to do the same trick in Europe. As recently as 2017, nearly 80% of cars sold in Europe were manuals, but by 2023 that figure had dropped to just 32%. Today less than a third of car models sold in the UK are even available with a manual transmission, such is the dominance of the auto.

You might think that’s because cars are mainly bought by non-enthusiasts – they’re little more than white goods to the majority of customers – but the evidence suggests that even car nuts are choosing autos over manuals these days. Ferrari introduced its first paddle-shift semi-auto model in 1997, and the last traditional stick-shift manual rolled off the line 15 years later in 2012. Lamborghini ditched manuals in 2014 and Aston Martin followed suit in 2021. This year’s new Porsche 911, a car that’s still the yardstick of enthusiasts’ vehicles for many, is the first generation to be launched without even the option of a clutch pedal and manual shifter.

So, a grim outlook for the manual motorcycle then? Not necessarily, for two key reasons. One is that the shift to automatic or paddle-shifted cars has come on the back of some key factors that don’t yet apply to bikes. One is the age-old adage of Win on Sunday, Sell on Monday, whereby motorsport influences customer demand. Racing cars in most major classes have used paddle shifts for close to 30 years (even more in F1, where the tech first emerged in 1989). That isn’t the case when it comes to bikes – autos and semi-autos are banned in all MotoGP classes – so riders who want to emulate their heroes will still want a manual shift.

That motorsport-influence halo is also used by car makers to mask the more real-world issues they face when it comes to meeting emissions and economy demands. Autos and semi-autos can be programmed to perform well in emissions tests, for example. Not in a dodgy, DieselGate style, but simply by optimising shift point and throttle responses to give the best performance under the test’s rules. Bikes might also face similar issues eventually, but not yet.

Finally, at the moment most of the semi-auto bike technologies in production or under development are very closely related to conventional manual boxes, which means there’s no real financial downside for manufacturers to offer both systems. If sales skew hard towards autos, it might become uneconomical to offer manuals as well, but at the moment the indication from Honda’s 15 years of DCT experience is that riders are split down the middle on their preferences.

Electric bikes like Zero’s DSR/X don’t need a clutch or transmission but the American company is working on pseudo-clutch to replicate the feeling of shifting gears

Electric bikes might make it a moot point

It’s safe to say that electric bikes haven’t yet made quite the splash in the market that many expected – and sales have actually been in decline over the last year or so – but with most manufacturers working on big EV motorcycle projects they could make the whole question of future automatic transmissions for ICE bikes a non-issue.

Electric bikes almost exclusively use a single-speed transmission. The motors have the ability to operate all the way from standstill to flat-out without needing to shift ratios, so why add the weight and complexity?

However, even in an electric future the experience of shifting gear might not disappear. At least two important players in the electric bike field – Zero and Kymco, which is partnered with LiveWire – have been working on simulated clutches and transmissions that can replicate the feel of a gearchange without requiring a real gearbox. It’s not the gimmick that it might initially seem. Electric bikes have the ability to offer endless options when it comes to regenerative braking and power delivery, and rather than forcing owners to wade through touchscreen menus to pre-select their preferences, a simulated gearshift and clutch offers the ability to continuously modify power delivery and engine braking in a way that today’s riders are instantly comfortable with. The manual gearbox might no longer exist in the future, but the manual experience looks likely to live on without it.

If you’d like to chat about this article or anything else biking related, join us and thousands of other riders at the Bennetts BikeSocial Facebook page.