How it works: Dual Clutch Transmission (DCT)

By Steve Rose

BikeSocial Publisher since January 2017.

02.07.2018

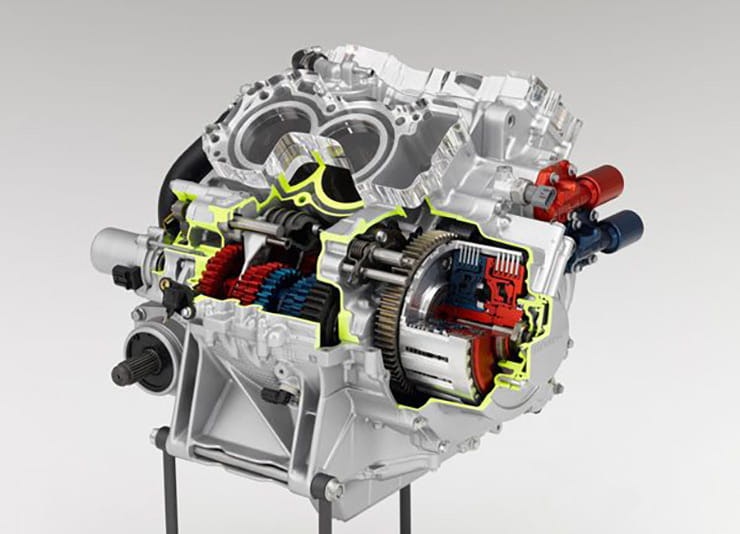

Above: The two clutches are to the far right, each driving the appropriate coloured gears. The red and blue tubes at the back of the engine are the electro-hydraulic actuators

Honda is quietly fitting its DCT to more and more bikes that started with the VFR1200 in 2010. It’s now an option on everything from the NC700 commuter to the latest Gold Wing and Honda even adapted it so that it works off road on the Africa Twin. A DCT for the Fireblade can’t be far away and you can bet other companies (especially BMW which has experience of DCT from its car division) are working on them too.

What is DCT?

Think of it as a manual gearbox controlled by a very slick robot. In manual mode you can tell it when to change up and down and you’ll get a very slick, fast change. In auto mode, the bike decides when to change (you can alter its aggression depending if you’re in Rain or Sport mode, for example).

What are the advantages of DCT?

There are two biggies. Firstly a DCT is more efficient than a manual because there’s less of a gap between gear changes which means less time spent with no power going to the rear wheel. So you go marginally faster, or get marginally better fuel economy. Secondly, even in manual mode, the rider has one less job to do because there’s no clutch to worry about, so riding is slightly less taxing. And of course DCT can be set in an automatic mode where all gear changing duties are taken care of.

VFR1200 was the first production bike with DCT in 2010

But what are the disadvantages of DCT?

Cost and weight. A DCT usually adds around £1000 and 10kg. Plus there’s extra complication and the associated potential for things to go wrong.

So what is it? An auto box, like in a car?

If you mean a traditional car auto that slushes from gear to gear with all the aggression of a cabbage, then no, a DCT is not like that. But if you’re talking about the latest generation of dual clutch autos that are fitted to almost every performance car these days then yes, the system is similar, though not exactly the same. Incidentally, Honda’s ’seamless shift’ system on its MotoGP bikes is something else again - that’s not a DCT.

So, how does DCT work?

The system has two clutches, one controlling the even gears, the other doing the odds. By swapping drive from one clutch to the other, and changing which gears they pass the drive to, the system can smoothly shift up or down extremely quickly. For example, to change down a gear without DCT, you’d pull the clutch in, knock the gear lever down one gear while perhaps blipping the throttle to match the revs of the new gear, then let the clutch out. A DCT will just pull one clutch in as it lets the other out because the lower gear has already been selected and is ready waiting. It’s the same deal on upshifts, where a DCT can shift fast and imperceptibly – it’s that good.

This is a cross-section through a first generation DCT. Honda’s next gen one has the clutches either side of the crank input gear

That sounds remarkably easy. Are you over-simplifying the mechanism?

Yes, a lot. Getting all this to work in the compact space available of a motorcycle is a technological feat. Honda’s system has the two clutch packs side by side (in cars they’re usually concentric, one round the edge of the other), with the pack nearest the gearbox driving a shaft that connects to 2nd, 4th and 6th. The outside clutch drive a shaft that runs within the other shaft (which is effectively a tube) and connects to 1st, 3rd and 5th (and 7th on the latest Wing). The two clutches are controlled by an electro-hydraulic system, which is itself controlled by the bike’s central computer (or ECU). So if you’re in Sport mode, the clutches will engage more aggressively for a faster, though slightly harsher change.

And how does it know which gear to engage next?

That’s the clever bit. The ECU knows whether you’re accelerating or decelerating, how much throttle you’ve got on (or how much brake) and what the load on the engine is. From this lot, and various other sensor inputs, it can make an accurate guess whether you will want a higher or lower gear next. You can fool it occasionally, but it’s rare – rolling towards traffic lights with the auto engaged for example, it will be changing down, expecting you to stop. But if the lights change and you gas it, it’ll have the wrong next gear engaged and there’ll be an electro-hydraulic panic which can result in a slight delay then a lurch as it eventually changes up. But that’s a rarity. Most riders with DCT keep it in auto all the time for good reason – it’s supremely effective.