10 wacky GP ideas

By Phil West

Freelance motorcycle journalist, former editor of Bike & What Bike?, ex-Road Test Editor MCN, author of six books and now in need of a holiday.

30.08.2016

GP bosses recently decided to ban, on safety grounds, the controversial aerodynamic ‘winglets’ which have became common in MotoGP machines this year – but not everyone’s in favour. Grand Prix racing is, after all, a ‘prototype’ formula intended to push the boundaries of technology although, in being so, not all the technical advances over the years have worked. Here’s our 10 of the most extreme – both good and bad!

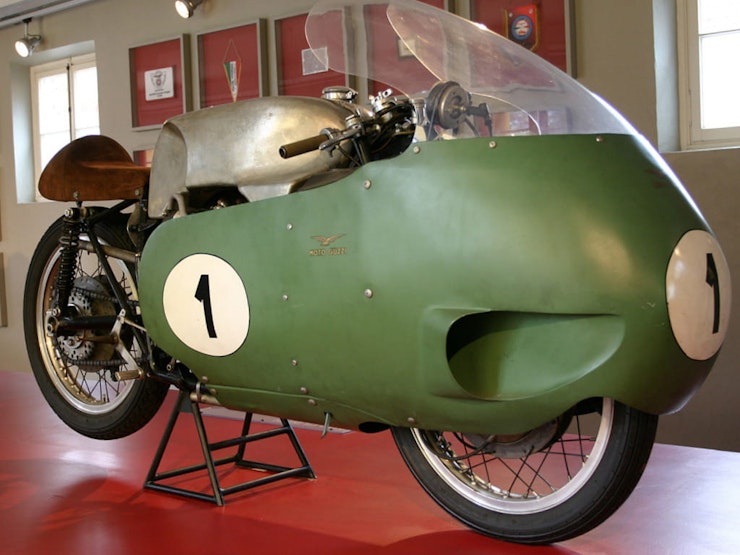

‘Dustbin’ fairings

Streamlined, front wheel-enclosing front fairings that resembled the nose of an aircraft and grew in popularity first in land speed record machines and, subsequently, on grand prix motorcycles. By 1957, all the leading factory machines sported them, most notably the radical new V8 Moto Guzzi, which posted speeds in excess of 180mph thanks to its aerodynamic help. However, due to fears about them causing instability, restricting steering and vulnerability to crosswinds they were banned by the FIM from 1958.

‘Oval’ pistons

Honda pulled out of GP racing in 1968 after just missing the 1967 500cc crown, in response to new technical regulations limiting the number of cylinders and gears. The four-stroke specialists returned in 1979 with its hugely ambitious NR500, which got around the four cylinder limit by creating, effectively, a V8 with Siamese ‘oval’ cylinders resulting in a V4, each with eight valves and, as Honda craved, the potential for a four-stroke to beat the reigning strokers. Enormous complexity including a 20,000rpm rev limit, ultimately destined it for failure, however.

Monocoque chassis

Various manufacturers have experimented with monocoque chassis, where, instead of a frame, a machine’s external skin forms its cohesive, load-bearing structure, but Kawasaki’s KR500 of the early 1980s is arguably the most famous. Dispensing with a frame the idea is primarily to shed weight. Instead, the first KR500, which debuted at the end of 1980 and went on to score two podium finishes the following year in the hands of Kork Ballington, used its aluminium fuel tank as its main structure with the steering head and swingarm pivot structures welded straight to it. Unfortunately, Kawasaki pulled out of GPs at the end of 1982.

Underslung fuel tanks

Honda may have replaced the NR500 with the relatively conventional two-stroke NS500 triple, but its follow-up, the first V4 NSR500 saw them back at their radical best. With the 1984 NSR, the traditional GP architecture of having the fuel tank atop the engine and exhaust pipes below was reversed – the idea being that the fuel’s weight would be carried low and the bike’s handling would alter less as the tank emptied. Unfortunately it didn’t quite work like that. While Freddie Spencer won the second round on the bike he opted to use the previous generation three-cylinder NS for the year and the idea was quietly abandoned.

‘Funny’ front-ends.

We couldn’t talk about radical GP tech without mentioning French firm Elf who, in the late ‘70s and ‘80s, supported a program of experimental racing machines distinguished mostly by novel, ‘frameless’ chassis with single-sided swingarm front suspension the prime idea being to lower the centre of gravity and eliminate fork dive. A series of endurance and GP machines followed, usually with Honda power (hence the Elf-branded ProArms on production bikes like the VFR750), the highlight being, arguably, the NSR500-powered Elf-4 of 1987 which Britain’s Ron Haslam took to fourth in the title chase.

Composite honeycomb frames

Invention is born out of necessity, they say, and never was it more true than with the 1984/85 Heron Suzuki 500GP machine. Suzuki Japan officially withdrew from GP racing after 1983 due to its RG500 square four engine, originally conceived in 1973, no longer able to keep pace with the latest V4 Hondas and Yamahas. However, it continued to support Heron Suzuki (in the UK) and Gallina (in Italy). Faced with a power deficit, Heron took the novel approach of commissioning a radical, ultra-lightweight frame comprised of aluminium sheets sandwiching a honeycomb material from CibaGeigy. The bikes raced for three years and gave GP debuts to Niall MacKenzie and Kevin Schwantz before being dropped when Suzuki officially returned with an all-new V4 in 1987.

‘Big 250s’

Italian firm Aprilia has always had racing ambition in its blood, particularly with the smaller 250cc and 125cc categories. Back in the mid-1990s, though, those two traits came together with a bang when it decided to take on the big 500 boys with what was effectively an enlarged 250. The idea was born from the realization that, at the time, Aprilia’s best GP250 twins could often post faster qualifying times than many of the four-cylinder 500s by virtue of being 25kg lighter. Aprilia duly produced a bigger ‘250’, the 410cc RSW2, to find out while Honda used similar thinking to produce its NSR500V twin. In reality, however, although quick in qualifying, in races the fours would blast past the twins on the straights then hold them up through the turns.

‘F1 style’ engines

The arrival of the new technical regulations for the renamed MotoGP class in 2002 was the catalyst for a whole new wave of technical experimentation – but few was as spectacular as that by Aprilia. For its first entry into the now four-stroke class, the Italian firm turned to F1 car specialists Cosworth to produce an engine, which was effectively three cylinders from a then-current V10 F1 engine. However, despite being one of the lightest and most powerful bikes on the grid, the ‘Cube’ as it became known (due to its RS3 designation) proved impossible to master and infuriatingly unreliable. Sadly the project was dropped in 2004.

Pneumatic valve springs

Although Aprilia’s ‘Cube’ had pioneered their use years earlier it took until 2008 for them to become more widely accepted, at least by the top teams. With the latest machines revving to 17,000rpm+ conventional metal springs aren’t reliable. Instead, while the valves are still opened conventionally, they are closed by a burst of high pressure nitrogen to push the valve stem back up. A regulator then lets the nitrogen out and the process can begin again – at over 140 times a second. Don’t expect them on road bikes any time soon.

‘Seamless shift’ gearbox

Honda pioneered this F1-derived technology in 2013 which essentially allows a new gear to engage before the previous gear disengages a process which not only shaves precious hundredths of a second off every gearchange (which can add up to a lot over the course of a race), but also, reportedly, makes the bike easier to ride and more stable not just under acceleration but under braking as well.

Share on social media: