Why the MOT test is an unsung hero

By Ben Purvis

Motorcycle Journalist

05.04.2023

The MOT test has been a staple of British motoring since 1960 and most of us simply accept it as something that’s part of vehicle ownership. But the Government is in the midst of a review of the testing process with an eye to making some of the biggest changes in its history.

Does it still achieve the targets it was established to hit, all those years ago? Will an updated system with less regular testing work make for a better compromise between cost, convenience and safety? Those are questions law makers are wrangling with at the moment. The Government has been consulting on the idea of changing the MOT requirements, asking whether there’s a case for extending the gaps between tests, but in doing so it might have inadvertently highlighted what a good job the existing MOT does.

The main thrust of the current proposals is the idea of extending the period between a vehicle’s date of registration and its first MOT, which was originally set at 10 years when the test was introduced but has been three years since April 1967 with subsequent tests annually throughout a vehicle’s life. While the MOT test itself has changed beyond recognition in the intervening 56 years, from a cursory check of brakes, lights and steering to an in-depth, nose-to-tail health check, the intervals between MOTs haven’t been altered in all that time.

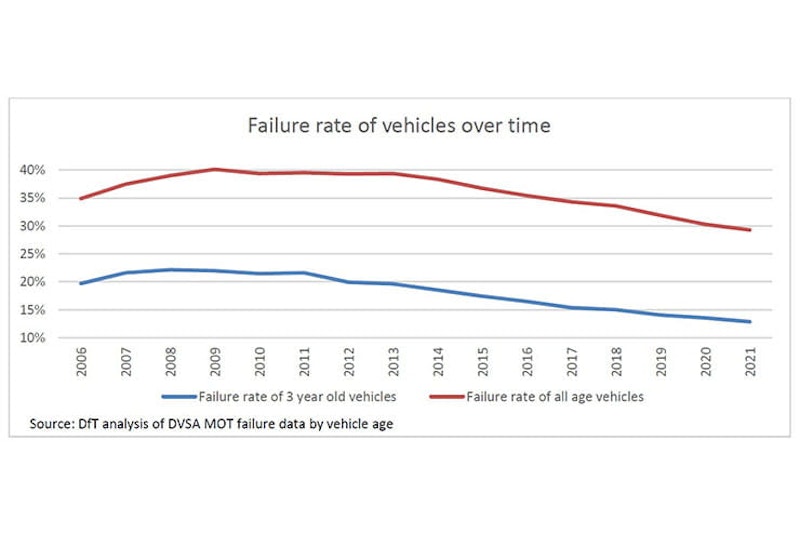

Fewer vehicles fail their MOTs now than ever before, so the Government is wondering if they need to be so regular

Why is the DfT looking at changing the MOT?

The ‘preferred’ option that the Government is considering at the moment is to extend the gap before the first MOT from three years to four, but it’s also looking at two other positions – one is to keep the current three-year test, the other to extend it further still to five years. The argument in favour of extending the time before the initial MOT is that today’s cars and bikes are more reliable than those made in the past, with a better pass-rate of that first test than ever before. Moving to four years rather than three would bring the system into line with many other countries including France, Ireland and even Northern Ireland, which already have a four-year gap before the first test.

It isn’t the first time the idea has been considered – the subject last arose in 2018 but wasn’t pursued beyond an initial consultation. Since then, initial pass rates for MOTs have improved across the board, bringing the question back into focus. With more vehicles passing their first MOT at the first attempt, the argument is that owners will benefit from reduced costs and hassle by putting that test off for an extra year.

The numbers that the Government assigns to these savings are remarkable. In MOT fees alone, the general public would spend around £900 million less if the test was put back by just one year, and nearly £1.8 billion less if the first test came at five years instead of three. Include savings to businesses and the estimated time saved in not having to travel to or wait for that first MOT at the three-year mark, and the numbers get higher still. Even after the loss of revenue to the DVSA from the tests is considered, as well as the costs of publicising the changes, the total benefit in terms of reduced public and business spending on MOTs is calculated at around £1.3 billion if the first test comes at four years, and more than £2.4 billion if it’s moved to five years.

It’s worth noting that the MOT doesn’t provide much income to the Government. The DVSA gets just £2.05 for each test, and that money is used for the authorisation of testers and the enforcement of MOT rules, so changing the frequency of testing doesn’t make a big impact on Government coffers. Most of the money involved in MOT testing goes to paying the garages doing the work, and since MOT test costs are capped, many garages might even be in favour of being able to spend the time currently consumed doing MOTs on more profitable repair work.

Mileage has a big impact on MOT pass rates

So, what are the downsides to a longer MOT gap?

It’s clear the Government is in favour of extending the gap before the first MOT to four years, but there are clear problems with putting off vehicle testing when it comes to maintaining road safety.

In 2021-22, around 29% of all vehicles failed their MOTs, with cars (29.21%) nearly twice as likely to fail as bikes (15.52%). In bare numbers, that amounted to 87,627 bikes and 7.3 million cars failing their tests. The numbers have dropped – in 2009, more than 40% of vehicles failed their tests – but MOTs clearly still show up a lot of problems that would otherwise go undetected. After all, presumably everyone who submitted their car or bike for a test believed it was roadworthy at the time.

Focussing specifically on the first MOT, at three years old, motorcycles are again the most likely to pass – with a failure rate of around 11% - while around 14% of three-year-old cars fail their first MOT.

The Government argues that there’s a relatively small increase in failures for four-year-old vehicles compared to three-year-olds (about 16% of four-year old cars fail, while motorcycles are actually more likely to pass at four than at three), which is why it favours moving the test.

However, that logic isn’t entirely sound. After all, the cars that failed their test at four-years-old passed an MOT just 12 months before, either at the first attempt or after repairs, so that means all those vehicles developed those faults in that fourth year. If there was no test at three years, the number failing at the fourth year would inevitably be higher than it is today.

It’s also worth noting the importance of mileage, as well as age. Average annual mileage of Britain’s vehicle fleet is dropping – particularly with the effects of the Covid pandemic and increased working from home. In 2021, the average mileage was around 5,500 miles per year. However, much of that is weighted towards younger vehicles, so in the flush of youth cars are likely to travel 10,000 miles per year or more. MOT failures rise in line with mileage even more reliably than with age: at 10,000 miles around 10% of vehicles of all types fail their test, but that rises to 20% by 38,000 miles, and by 100,000 miles the failure rate is north of 40%. A four-year-old car could very easily have covered 40,000 miles or more before an MOT tester gets his first look at it. More than enough to develop substantial faults, particularly for critical wear items like tyres and brakes.

And defects can mean deaths. In 2011, the Transport Research Laboratory (TRL) conducted research to corollate fatalities with vehicle defects. Its findings were in line with what we’ve come to see from the MOT statistics – that motorcycles are likely to be well looked-after, while dangerous faults were more common in cars. Based on figures from 2009, it estimated that just 0.73% of motorcycle-related fatalities were due to vehicle defects, compared to 2.36% of car-related fatalities. The total number of motorcycle accidents due to defects was a mere 0.32%, while 2.67% of car accidents could be attributed to mechanical problems. While the MOT failure rate for cars has dropped since then – from 40.6% to 29.21% - faults that would be picked up by an MOT test can only increase if the initial test interval is extended from three years to four.

The extension of the gap between tests doesn’t only increase the number of faults that might arise on vehicles being used on the road, but also everyone’s exposure to that danger. A car that develops an MOT-failing fault at 2 ½ years old – worn brakes or tyres, for instance – with an owner who’s unaware of the risk, would currently be on the road for a maximum of six months before the fault was found at its MOT. With a four-year first test interval, that situation could go on for 18 months, and if the five-year first test option is selected, the car could be posing a danger for half its lifetime before the problem is picked up.

In terms of bare figures, the Government’s own estimates are that casualties due to vehicle defects could rise by between 1% and 4% if the first MOT was at four years rather than three, with between 16 and 65 additional injuries, although the number of additional annual deaths likely to arise from the change is far lower, estimated at between zero and one per year. Since cars make up the majority of traffic, the majority of MOT tests (94% of them) and have the majority of accidents, that’s where the increase is also expected to come. Looking at bikes alone, the shift to a four-year gap to the first MOT is estimated to result in zero additional deaths, between one and four serious injuries and between two and seven slight injuries, with a worst-case scenario of 11 extra casualties of all severity and no additional fatalities.

Motorcycles over 200cc (‘Class 2’ vehicles) have the best pass rates of all. Cars (‘Class 4’) get much worse with age.

How do people feel about changing the MOT rules?

You might have thought that saved time and effort that the Government highlights with its preferred option of extending time before the first MOT from three years to four would be a hit with the non-enthusiast public, saving them hassle and money related to that test, but a poll of drivers suggests they’re against it.

The Savanta poll, carried out on behalf of the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Trader (SMMT), asked 1,784 car users what they thought, and two thirds (67%) of respondents were against extending the period before the first test.

The SMMT also points out that we had a glimpse at the effects of extended MOT intervals when the Covid pandemic put a temporary halt to testing and vehicles with tests due at that time were given an automatic extension to their MOTs to make up for it. Even though car use was vastly lower over the same period, failure rates increased by between 2% and 3%.

For many, the MOT also provides a regular opportunity to have an expert cast an eye over their car or bike, picking up on upcoming faults even if they pass. These advisories mean problems can be fixed before they become a bigger, more expensive issue. Those repair costs could easily outweigh the relatively meagre savings made by extending the first MOT period from three years to four. Figures from 2016-2022 show that across all vehicle types, the failure rate of those that are MOT tested between three- and eight-months overdue rises to 42%, substantially higher than the failure rate for those that are MOT’d on time (which averaged 34% across the same period).

Insurance is another consideration. The Government’s own impact assessment suggests that the option of moving the first MOT to four years instead of three could increase the collision rate for vehicles by between 1.55 and 1.6%. While the research doesn’t estimate how much that could lead to an increase in premiums, it’s worth noting that the vehicles involved in those accidents would be newer ones, presumably under four years old and yet to reach their first MOT, which means they’d also be among the most valuable. Whether written-off or repairable, the chances are the impact on insurance pay-outs would reflect the relatively high value of those vehicles, so the rise in premiums could well exceed the 1.55% to 1.6% overall rise in collision rates.

Cars (Class 4) make up the lion’s share of MOT tests, while bikes (Class 1 under 200cc, Class 2 for the rest) total just 3%

Environmental impact

Over 10 years, the Government estimates a change from three to four years for the first MOT would save an estimated 39,500 tonnes of CO2 being put into the atmosphere from travelling to and from tests.

However, that could be more than offset by the fact that emissions are a common MOT failure point. If vehicles under four years of age have faults in their emissions systems, or simply engine problems that lead to increased emissions, then they could be getting used for an extra year on the road before those faults are picked up on. Around 3 percent of cars fail MOTs on emissions – that might not sound like many but bear in mind that there are more than 31 million cars tested each year, and 3% of that is around 950,000 . In 2020, some 1.3 million vehicles of all types failed their MOTs due to exhaust emissions.

How do bikes fit in with the proposed changes?

As some of the most vulnerable road users, motorcyclists are likely to be threatened most significantly by any increased risk that’s introduced by changes to the MOT. Being caught up in an accident caused by another vehicle’s lack of roadworthiness is a scary prospect.

Ironically, bikes would actually be by far the best-placed vehicles to have gaps between their MOTs extended. Generally, they cover fewer miles between tests, they have the best pass rates of any vehicle subject to MOTs and they have enthusiastic owners who are likely to be clued-up on maintenance and vividly aware that skimping on things like tyres or brakes could carry a high personal cost. With relatively few components compared to cars, and all the main mechanical bits clear to see, problems are easier to pick up and resolve before they become a more serious issue.

That’s demonstrated by the fact that even at 20 years old, a bike is more likely to pass its MOT at the first attempt than a five-year old car.

Given that extending the first MOT to five years is an option that the Government is considering, you could argue – with facts and figures to back up the position – that motorcycles should be exempted from the MOT test altogether. The last big shake-up of MOT rules was the 2018 law change that allowed ‘Vehicles of Historic Interest’ – which can be most cars and bikes over 40 years old – to be exempt from MOTs. The logic applied to that change was that classic cars don’t cover huge mileages (like most bikes), their owners are enthusiastic and knowledgeable (like most motorcyclists) and their MOT failure rate, at 22.6%, was far lower than normal cars. The initial failure rate for ‘Class 2’ motorcycles (over 200cc) is 14.2%, and for both Class 1 and Class 2 bikes combined in 2021-22, it was still only 15.52%, well below the level that saw 40-year-old vehicles get exemption five years ago.

The idea of exempting bikes isn’t on the table, though, and most riders would probably be against it even if it was – a sense of self-preservation means getting an expert eye over your bike once a year isn’t something many riders object to.

However, the possibility that the annual test could be extended to a biennial one is under consideration. While the Government doesn’t have a particular position on the subject, its most recent consultation has asked respondents their thoughts on a 24-month gap between tests, asking individually about each class of vehicle, including bikes, whether the MOT should be annual, biennial or biennial for the first decade, with annual tests for older vehicles over 10 years of age.

Vehicle defects led to 1455 injuries in crashes in 2019

The MOT: a undervalued contributor to road safety

The strength of feeling about making the MOT less frequent won’t be known until the results of the Government’s consultation are released – likely to be later this year – but the facts and figures presented alongside the proposed changes don’t seem to convincingly support the idea that the gaps between tests should be increased.

Nearly a third of all MOT tests result in failure (although the figure for bikes is vastly lower than that) and while that might be an annoying inconvenience if your vehicle is part of that statistic, it’s also a clear indicator that the system works. An extension of the gap between MOT tests, whether in the form of a four-year wait for the first test or shift to biennial testing thereafter, can only result in an increase in the number of dangerous vehicles on the street.

The DfT’s data shows that vehicle defects are a contributory factor in only 1.5 – 1.7% of crashes (based on 2019 figures, which aren’t skewed by any effects of the pandemic and the MOT extensions that were handed out during it). However, that’s still 1,455 people injured by accidents involving defective vehicles that might have been picked up at an MOT. The Government’s impact assessment says that number represents a 38% drop since 2010, suggesting vehicles are becoming less susceptible to dangerous faults, but it’s still a large number of avoidable crashes, and one that can only rise if MOT testing is made less regular.

Whether the Government will follow the findings of the consultation or, as with the decision to end MOT testing for historic vehicles, go against the tide of opinion to follow its own ‘preferred’ path, will become clear only once the responses have been assessed.

If anything, the numbers go to show how valuable annual vehicle testing is, ensuring that our bikes and cars get an expert appraisal on a regular basis, and more importantly helping to prevent those who are less aware of their own vehicles’ requirements don’t sleepwalk into problems. Most road users have no more passion or interest in their vehicles than they have in the inner workings of their fridge-freezers, and the MOT test does a remarkable job of keeping them roadworthy. It’s something we should treasure, not diminish.