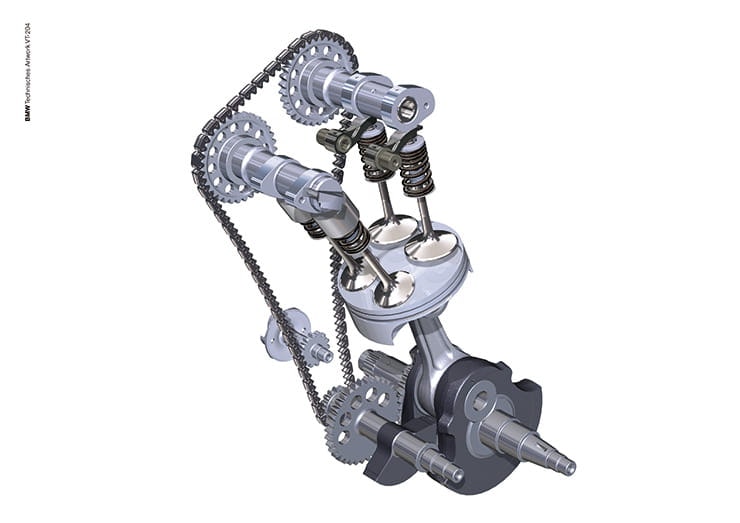

On this BMW G450X engine the inlet valves are bigger than the exhausts to aid a air/fuel flow

These little chaps – full name: poppet valves - control the entry and exit to the combustion chamber. They open to let the air and fuel mixture in, close to seal the chamber when the mixture explodes so the piston is forced down, then another set opens to let the exhaust gases out. Most modern bikes have four valves per cylinder (two for inlet, two for exhaust) though various Yamahas have five (three inlets), which if you’ve ever had to buy shims for them, can make it rather expensive.

These are from the new KTM 790 Duke. Note the smooth shape from the stem to the face – that’s important to get gases in and out quickly

What are valves?

All motorcycle poppet valves are shaped like a 4-inch nail with a big flat head. In modern bikes the valve’s head (called the face) sits in the combustion chamber with the shaft (called the stem) poking up out of the cylinder, where it is attached to a spring.

How are they operated?

On top of the valve is the opening mechanism of your choice – some engines use a rocker arm to connect to the camshaft (bevel Ducatis), others use a finger (eg BMW R1200GS), others a bucket (almost every Japanese four-cylinder), with the camshaft directly above it.

There are other ways of activating the valves – some older engines have rocker arms connected to a pushrod which is operated by cams down by the crankshaft, and modern Ducatis use a Desmodromic system (we’ll tackle that another day).

But let’s stick with the most common configuration – the double overhead cam (DOHC), with one of the two camshafts operating two inlet valves per cylinder, the other doing the two exhaust valves per cylinder.

How it works

In theory, the valve operation is very simple: the cam pushes the valves down into the cylinder against the spring, opening the valve so gases can flow and then lets the valve shut under the force of the spring. The pressure in the combustion chamber rather neatly helps seal the valve shut.

Problems are caused because of the number of times this has to happen. With a bike engine revving at 10,000rpm, for example, each valve has to open and close 83 times a second, so it has to move fast. This speed is a problem, because it means the valve has a lot of energy and is repeatedly slamming into the valve seat.

There’s not much you can do about this – if you make the spring weaker, so the valve doesn’t slam as hard, the valve will eventually lose contact with the cam and won’t open at the right time. If you reduce the distance the valve has to travel, so the valve has less run-up for its headbutt into the valve seat, less gas can get in or out of the combustion chamber which reduces power.

The only solution is metallurgy – make stronger and lighter valves that can withstand all the slamming, and the combustion chamber’s heat. Hence the use of titanium valves in some sportsbike motors (eg the 2017 GSX-R1000).

You really don’t want to be replacing all the shims on the BMW’s K1600!

It’s all about timing

Valve timing is critical. By changing the orientation of the cam lobes and their profiles, engine designers can set exactly when the inlet and exhaust valves open, how long they stay open, and when they close. This has a huge effect on where peak torque and power occur in the rev range.

For example, for a Harley V-twin you want loads of torque low down the rev range, so you set the valve timing to be as efficient as possible at low revs. Things aren’t moving too fast at those revs, so, for example, you can open the inlet valves later and close them earlier to extract as much energy as possible when the gas explodes. Ditto with the exhaust valves so the time when both inlet and exhaust valves are both open (the overlap) is small.

The problem with this is that as revs increase, there’s not enough time to get all the mixture you need in, and all the exhaust out. So, from the rider’s perspective, the engine runs out of puff. On a high revving four-cylinder engine designed for maximum power, it’s the opposite – you set the valve timing for high revs, when everything is moving very fast, so inlet and exhaust valves need to be open for a greater percentage of the stroke cycle to make sure you get plenty of mixture in and then get all the exhaust out. That’s fine, but at low revs it can be horribly inefficient.

The answer of course is variable valve timing… you can read more about that here.