BMW rewrites the rules on motorcycle safety

By Ben Purvis

Motorcycle Journalist

03.08.2020

By opting to ride a bike instead of taking the car we make certain compromises in terms of safety – sacrificing a protective cage in favour of manoeuvrability and performance – but BMW is developing a system that gives the best of both worlds in the form of a removable safety cell for two-wheelers.

Such is the idea’s novelty that last month alone BMW filed a tranche of 15 patent applications for different aspects of the design; not only demonstrating how innovative it is but also showing that the firm is pumping money into its development. This isn’t just idle doodling on the part of a bored engineer.

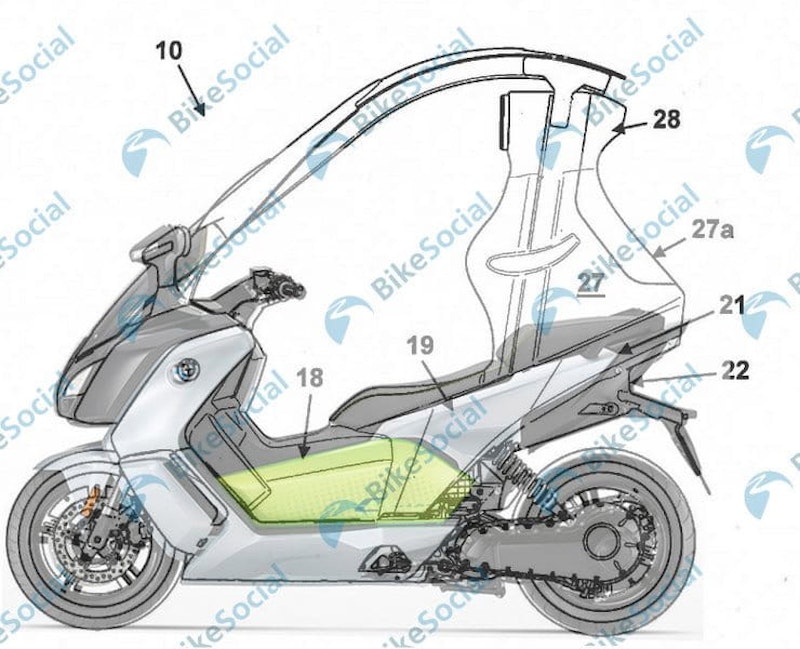

Last year’s patent, above, showed a roof on the C Evolution electric scooter

We first got a glimpse of BMW’s thinking more than a year ago when the firm filed a patent for a roof structure designed to bolt onto its C Evolution electric scooter. Now the new documents show that the idea has gained traction at BMW, fleshing out the concept and revealing a host of details about how it works.

While BMW has travelled this road before with the unloved C1, which went on sale 20 years ago and disappeared from the market just two years later after disappointing sales, the firm has learnt from that experience and addresses the problems in its new design.

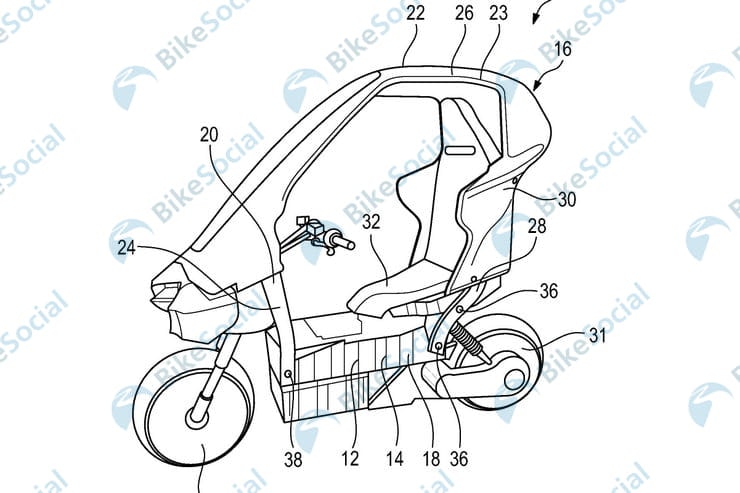

Just a few bolts hold the whole top in place

The most important change compared to the C1 is that the crash structure in the new patents is removable. By pulling out just a handful of bolts, the roof, screen, seatbelts, seat back and all the associated safety features can be detached and left at home, leaving a relatively conventional bike – albeit an electric one. So your dull commute can be done in safety – and thus without the need for extensive riding kit or even a helmet in many countries – but at the weekend you can remove the safety cell and have a lighter, higher-performance, open-air bike to have fun on.

The second problem with the C1 was weight; at around 185kg it had the mass of a 1000cc superbike but the power of a 125cc scooter, a recipe for sluggish performance and dull-witted handling. Again BMW has aimed to solve that problem, swapping the aluminium of the C1’s safety cell for a carbon-fibre design.

Crumple zones allow roof to be pushed down in impact, absorbing energy

Two carbon-fibre hoops form the basis of the safety cell and roof. They’re slightly flexible, allowing them to dissipate impact forces, and bolt onto the bike at the front and rear via collapsible ‘crumple zone’ components (numbered ‘40’ in the image above) that crush in the event of an impact from above to further absorb crash energy.

However, they’re not the only line of defence in the event of a crash. BMW’s patent also shows the bike to have seatbelts, with two inertia-reel belts – one over each shoulder – allied to pre-tensioners that tighten the belts in a crash. There are also side airbags built into the shoulder areas, which expand to become hip-to-shoulder protection during a crash, simultaneously preventing your arms from flailing outside the safety cell.

The seat back, which is part of the removable roof, also has impact-absorbing pads to help protect your spine if the bike is rear-ended. BMW has even considered issues like screen misting, building in an air vent that directs fresh air from the nose up onto the inside of the windscreen.

Active aerodynamics mean there’s preventative safety as well as crash protection

While the use of carbon fibre helps address the top-heaviness that plagued the C1, the sail-like shape of the structure will inevitably make the bike more susceptible to side-winds than a conventional two-wheeler.

BMW has thought of that, too, and added a system of active aerodynamics to help counter external forces that try to push the bike off line or tip it over. Four active winglets (labelled ‘32’ in the image above) are fitted – two on the front near the base of the windscreen and two more level with the rider’s shoulders. As well as creating downforce, these act like an aeroplane’s ailerons by altering their angle in response to inputs from the bike’s IMU and stability control system. Should a side-wind start to push the bike off line, the winglets are designed to counter that force, so the rider – who’s understandably unable to move his weight quite like you might on a normal bike – doesn’t feel its effect or need to compensate for it.

Winglets (above) move automatically to counter side-winds and increase stability

Underneath all this tech lies the same chassis and electronics used on the BMW C Evolution – the firm’s decent, if pricy, electric scooter. That bike’s aluminium, platform-style chassis, incorporating the weight of the batteries low down, should help offset the high-mounted mass of the roof structure.

That basis suggests this won’t be a cheap machine should it reach production. The C Evolution is already a hefty £14,330, and the addition of a technology-packed, carbon-fibre roof, complete with airbags, seatbelts, tensioners, active winglets and crumple zones, can only add significantly more.

However, if considered a viable commuting alternative to a few years’ worth of rail season tickets, with its easy parking and car-like safety and weather protection, there’s a good chance buyers prepared to pay £20k or so for such a bike might emerge, particularly in a COVID-19 landscape where the prospect of public transport is less attractive than ever.

Share on social media: