Kawasaki developing dual-injected supercharged engine

By Ben Purvis

Motorcycle Journalist

14.01.2020

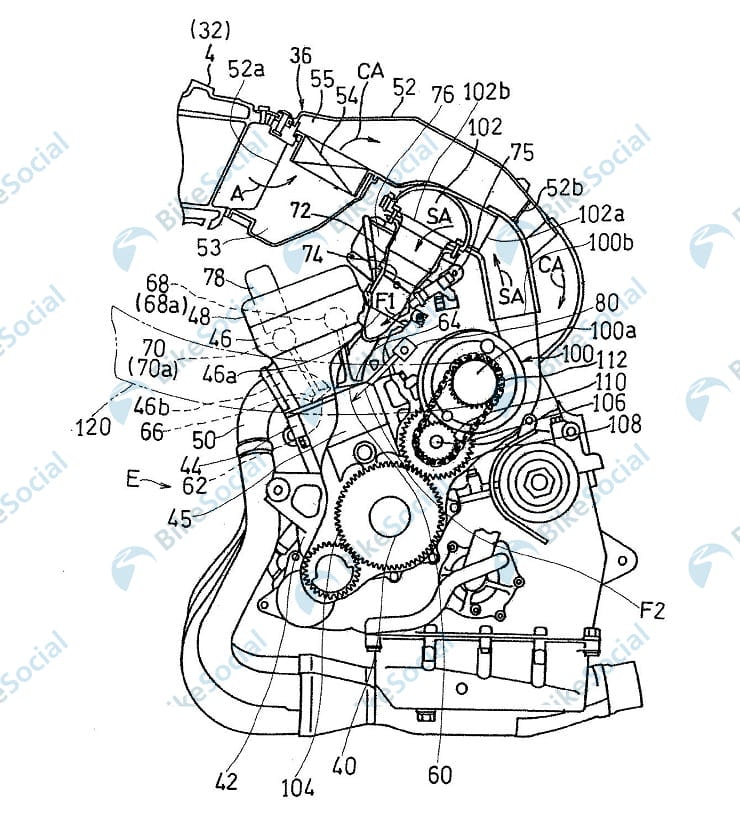

Kawasaki’s dual fuel injection system is seen here fitted to a supercharged four-cylinder engine

Direct fuel injection is already becoming the norm for car engines that need to beat tough Euro 6 emissions limits and it won’t be long before the same technology gets applied to bikes.

We’ve already seen evidence that Honda is developing direct fuel injection, using a modified Africa Twin engine, and now patent applications have been published showing that Kawasaki is also working on a direct-injected engine. This time, the supercharged four-cylinder motor used in the H2 is the guinea pig for the system, and rather than switching wholesale to direct fuel injection Kawasaki’s intention is to combine the technology with conventional port fuel injection to get the best of both worlds.

High pressure fuel supply for the DI system comes from a pump driven by the exhaust camshaft (78), feeding the direct injectors (80)

Direct fuel injection isn’t a new idea, but it’s one that so far hasn’t made the leap to motorcycles. Normally, fuel injected bikes use ‘port’ injection, where the fuel is squirted into the intake port upstream of the intake valve but after the throttle butterfly. That means the fuel and air begin to mix before entering the combustion chamber, giving plenty of time for the fuel to atomise and combine thoroughly with the intake air before the spark plug fires to ignite the mixture.

Direct fuel injection works differently. As its name suggests, it squirts petrol directly into the combustion chamber. Both systems have pros and cons, and Kawasaki’s plan to combine the two aims to maximise the advantages and eliminate the downsides.

Combination of port and direct fuel injection promises best of both worlds

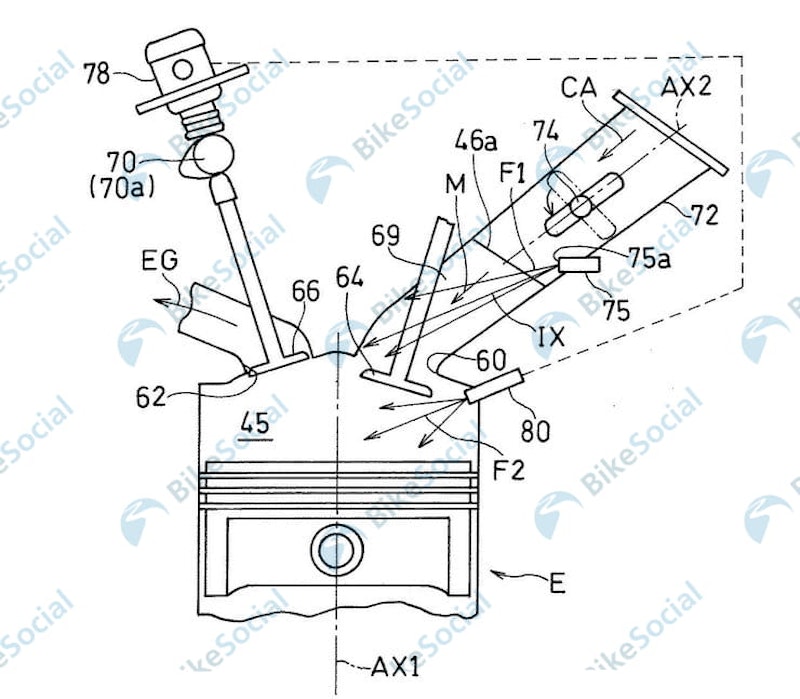

This image shows Kawasaki’s dual-injector system fitted to a normally-aspirated superbike engine

The slow adoption of direct fuel injection (DI) on bikes comes down to a combination of factors. Most notably, DI injects fuel much later than port injection, giving less time for fuel and air to mix before it’s ignited. Since motorcycles typically rev much higher than cars that’s a significant problem; DI systems that can cope with a car engine revving to 7000rpm won’t necessarily be able to work with a bike motor spinning twice that fast.

In recent years injector and combustion chamber has overcome that problem, with many racing designs including F1 cars adopting DI despite bike-high revs. That means we’re fast approaching the point when we’ll start to see direct-injected motorcycles.

Another factor is simply demand. Cars already face tougher emissions limits than bikes – needing to meet Euro6 limits in Europe where motorcycles are only just starting to adopt Euro5. As long as manufacturers can meet the limits without needing to adopt new technology, there’s little impetus for them to develop or adopt it. However, with Euro5 now a reality on two wheels, attention has turned to the Euro6 rules that will follow, and which are sure to add pressure to adopt DI.

Direct fuel injectors (80a) fire towards the centre of the combustion chamber

Both port-injected and direct-injected engines have their own advantages, each tied into the cooling effect that the fuel has when it’s added to the intake air.

On a conventional port-injected engine, the fuel considerably cools the intake air before it’s allowed into the combustion chamber. Since cooler air is denser, by reducing the temperature before the air is drawn into the cylinder, more air – and hence more oxygen – is sucked in with each intake stroke. That’s good for power. Direct injectors, which add the fuel after the air has been sucked into the cylinder, can’t offer this cooling advantage.

However, DI’s cooling gives a different benefit. It directly cools the combustion chamber and the piston, which reduces the chance of detonation – or ‘knock’ – when the mixture is ignited. That means you can use a leaner mixture or, on a turbo or supercharged engine, more boost, without the risk of potentially damaging knock. That means more power, better fuel consumption and lower emissions.

Last year, Honda patented its own direct injection system, illustrated on an Africa Twin (above)

Since both types of injection have their own advantages, Kawasaki’s patent proposes using both to give a combination of the two systems’ benefits.

It’s not the first company to use the idea. Toyota has made cars with both port and direct injection for years, and VW/Audi does something similar, but it hasn’t been seen on bikes before.

On the existing dual-injected designs the engine management alters the injection to change the emphasis between port and direct injection depending on revs and throttle openings. Kawasaki will surely follow the same route. Port injection tends to be used at lower revs, with DI taking on more responsibility at high engine speeds, with the engine management computer mapped to alter their behaviour depending on a host of variables.

Combining the two systems means that you can use the port injector to introduce a very lean mixture of fuel and air, with plenty of time for the fuel to atomise and mix, cooling the intake charge. The direct injector then adds an additional dose of petrol later in the cycle, during the compression stroke, to give a richer mixture that’s focussed around the spark plug. The rich part is easy to ignite, and once burning it makes the leaner mixture around it start to combust.

Audi’s dual injector system, pictured above, is very similar to the Kawasaki design

Kawasaki’s new patent shows its combined direct-and-port-injection system fitted to both a supercharged four-cylinder motor, similar to the Ninja H2’s design, and to a normally-aspirated four more like the Ninja ZX-10R’s. Both types of engine could benefit, but the supercharged motor stands to get the most from the direct injection, allowing more boost to be used without increasing the risk of engine damage.

The firm overcomes the problem of high fuel pressure needed for the direct injection part of the system by adding a mechanical fuel pump operated by the exhaust camshaft to the system. This pump only feeds the direct injectors; a conventional electric fuel pump gives a relatively low pressure supply to the system’s port injectors

Share on social media: