Harley-Davidson developing Variable Valve Timing

By Ben Purvis

Motorcycle Journalist

24.07.2020

For years naysayers have predicted the impending death of the traditional air-cooled Harley-Davidson V-twin as ever-tighter emissions rules threaten to squeeze the last wheezing breath from the old-school designs – but new patents from Harley show that at least one more completely new generation of air-cooled twin is on the way.

Despite the doomsters, old-fashioned air-cooled, cam-in-block engines are far from dead. Just this year BMW has unveiled its first such design in decades in the form of the new R18, a bike that’s intended to live on for at least a decade, and we’ve spoken before about how big, low-revving cruiser engines could actually be winners in the battle to reduce emissions. By putting R&D funds into a new air-cooled twin, Harley-Davidson is showing that despite plans for more electric bikes and greater diversity in the future, along with the new Revolution-Max-powered water-cooled V-twin models, it’s not about to abandon its core buyers.

The most significant element of the engine featured in Harley’s new patent applications is the adoption of variable valve timing.

It’s actually particularly simple to add VVT to a pushrod, cam-in-block engine because a single actuator can simultaneously advance or retard all the valve timing, both intake and exhaust.

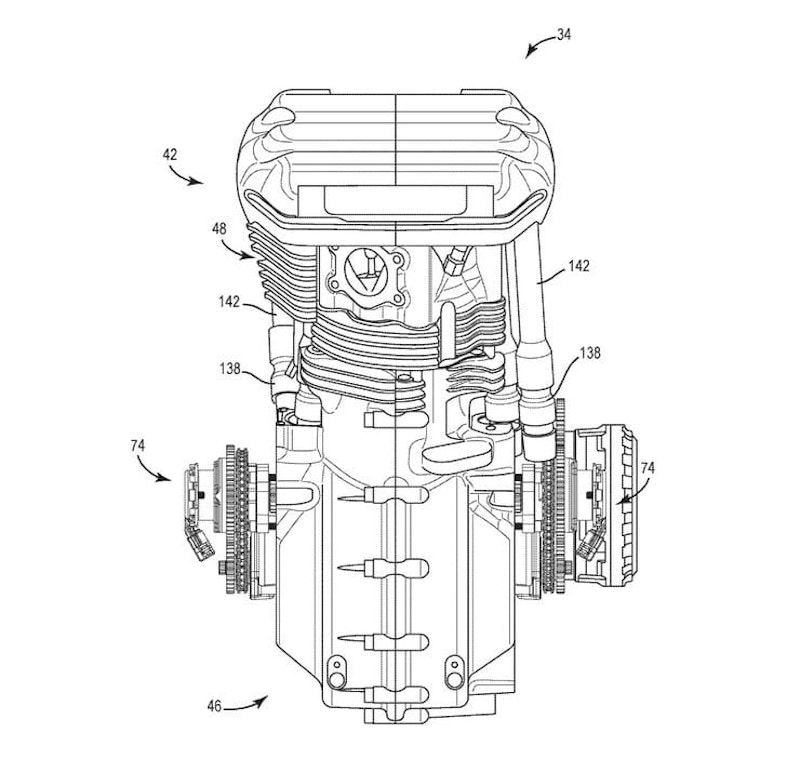

Like other Harley engines, this is a twin-cam design, gear-driven from the crankshaft. The VVT actuator is mounted on the intermediate gear that reduces the camshaft speed to half that of the crankshaft.

Unusually, the pushrods aren’t sited together on the right hand side of the engine, as is the norm. Instead, there’s a pushrod on each side of each cylinder – four in total. On the front cylinder the right hand pushrod operates the inlet valves and the left hand pushrod actuates the exhaust valves. The same setup was also shown on another patent for the new engine, filed last year.

The Harley design isn’t the first time we’ve seen VVT like this on a pushrod, air-cooled engine. Indian filed patents for a similar idea last year, with a very similar setup, again putting the VVT actuator on the intermediate gear between the crankshaft and camshafts.

Like the Indian design, Harley’s engine uses a very conventional VVT actuator, much the same as the units used on Ducati’s DVT variable valve system and dozens of cars. Oil pressure is used to shift the output side of the actuator by a few degrees in relation to the input side. A solenoid operated by the engine management unit opens or closes the oil passages to the actuator, letting oil into the chambers inside it that cause the shift.

If it’s so conventional, you might wonder what Harley’s trying to patent? It’s not actually patenting the VVT system at all, but a form of crankshaft balancer that’s driven by the camshaft intermediate gear.

The intermediate gear (and thus the VVT actuator) is gear-driven from the crankshaft, so turns in the opposite direction. It’s twice the size of the crankshaft gear, so turns at half the speed. However, a chain sprocket is also attached to the intermediate gear, running back down to a smaller sprocket that’s concentric with the crankshaft. That smaller sprocket turns a balancer weight. Because the intermediate gear is turning in the opposite direction to the crank, the balancer spins at the same speed as the crankshaft but in the other direction to offset unbalanced forces from the crank.

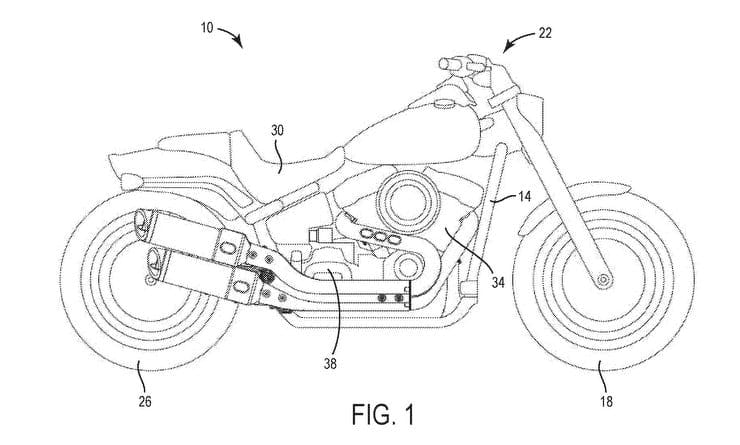

The big question is what bikes the engine is destined to be used in. That’s not clear at all. Harley’s patent shows the outline of Fat Bob, but since that model is powered by the relatively new Milwaukee-Eight V-twin it seems unlikely that it – or the rest of Harley’s ‘big’ V-twins – are in the most desperate need of a new motor. Instead this engine could be intended as a replacement for the smaller 883 and 1200 V-twin used in the Sportster range. Not only is the Sportster engine much older than the Milwaukee-Eight – the current model can be traced back to the Evolution of 1986 – but smaller, higher-revving engines often benefit more from VVT than larger-capacity designs, so the Sportster motor would be a more suitable target for the system than the bigger V-twin.

Share on social media: